On November 5, 2024, Republican Donald Trump was reelected president of the United States, with J.D. Vance elected to the vice presidency. Trump is only the second president – after Democrat Grover Cleveland in 1892 – to lose reelection then win again four years later. Trump also became the first Republican presidential nominee to win the popular vote since George W. Bush in 2004, albeit falling just short of a majority with 49.7% of the nearly 155.6 million votes cast. The Democratic ticket of Kamala Harris and Tim Walz won 48.2% of the vote, with the remaining 2.1% divided among several third-party candidates. After increasing by 15.6% from 2016 to 2020, turnout dropped slightly (1.9%) from 2020 to 2024.

Trump-Vance won the popular vote by 1.5 percentage points (“points”), or 2.3 million votes, but they captured the White House because they won the Electoral College. The Republican ticket won 312 Electoral Votes (“EV”) – 42 more than necessary – while Harris-Walz won 226. In one sense, then, 2024 was a rerun of Trump’s and Mike Pence’s 2016 victory over the Democratic ticket of Hillary Clinton and Tim Kaine, except Nevada’s 6 EV flipped from Democratic to Republican.

However, Clinton-Kaine won the popular vote by 2.1 points (48.0% to 45.9%), and 2.9 million votes, while third parties earned 6.0% of the vote. Even worse, Harris-Walz had a lower margin than the 2020 ticket of Joe Biden and Harris in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with an average decline of 4.3 points (median = 3.9). Harris-Walz performed at least eight points worse than Biden-Harris in six states: Texas (-8.1), Massachusetts (-8.3), California (-9.0), Florida (-9.7), New Jersey (-10.0) and New York (-10.6).[1]

Adding insult to injury, while Harris easily won her home state of California, she and Walz received 1.8 million fewer votes there than Biden-Harris had in 2020; Trump gained 75,179 votes. That sharp decline in turnout likely cost the Democrats two seats in the United States House of Representatives (“House”), in a year they fell three seats short of regaining the majority. Turnout also dropped by more than 300,000 in three other large Democratic states: Illinois, New Jersey and New York.

That all said, Harris-Walz lost less than two points relative to Biden-Harris in eight states: North Carolina (-1.9), Oregon (-1.8), Wisconsin (-1.5), Kansas and Nebraska (-1.4), Oklahoma (-1.2), and Utah and Washington (-1.0). Had just 229,766 votes shifted from Trump-Vance to Harris-Walz in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin in 2024, the Democratic ticket would have been the first to win the EC (270-268) while losing the popular vote. This makes 2024 the third consecutive presidential election in which a relatively small number of votes in these three states determined the outcome. Table 1 below shows there were only seven other close states in the last two presidential elections – though Florida is no longer remotely a swing state.

Table 1: States with Presidential Election Margins <5.0 Points in 2020 and/or 2024

| State | EV | 2020 Margin (Dem-Rep) | 2024 Margin (Dem-Rep) | 2020-2024 | |||

| % | # | % | # | % | # | ||

| Florida | 30 | -3.4 | -371,686 | -13.1 | -1,427,087 | -9.7 | -1,055,401 |

| Arizona | 11 | 0.3 | +10,457 | -5.5 | -187,382 | -5.8 | -197,839 |

| North Carolina | 16 | -1.3 | -74,483 | -3.2 | -183,048 | -1.9 | -108,565 |

| Nevada | 6 | 2.4 | +33,596 | -3.1 | -46,008 | -5.5 | -79,604 |

| Georgia | 16 | 0.2 | +11,779 | -2.2 | -115,100 | -2.4 | -126,879 |

| Pennsylvania | 19 | 1.2 | +82,166 | -1.7 | -120,266 | -2.9 | -202,432 |

| Michigan | 15 | 2.8 | +154,181 | -1.4 | -80,103 | -4.2 | -234,284 |

| Wisconsin | 10 | 0.6 | +20,682 | -0.9 | -29,397 | -1.5 | -50,079 |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 7.4 | +59,277 | 2.8 | +22,965 | -4.6 | -36,312 |

| Minnesota | 10 | 7.1 | +233,012 | 4.2 | +137,947 | -2.9 | -95,065 |

**********

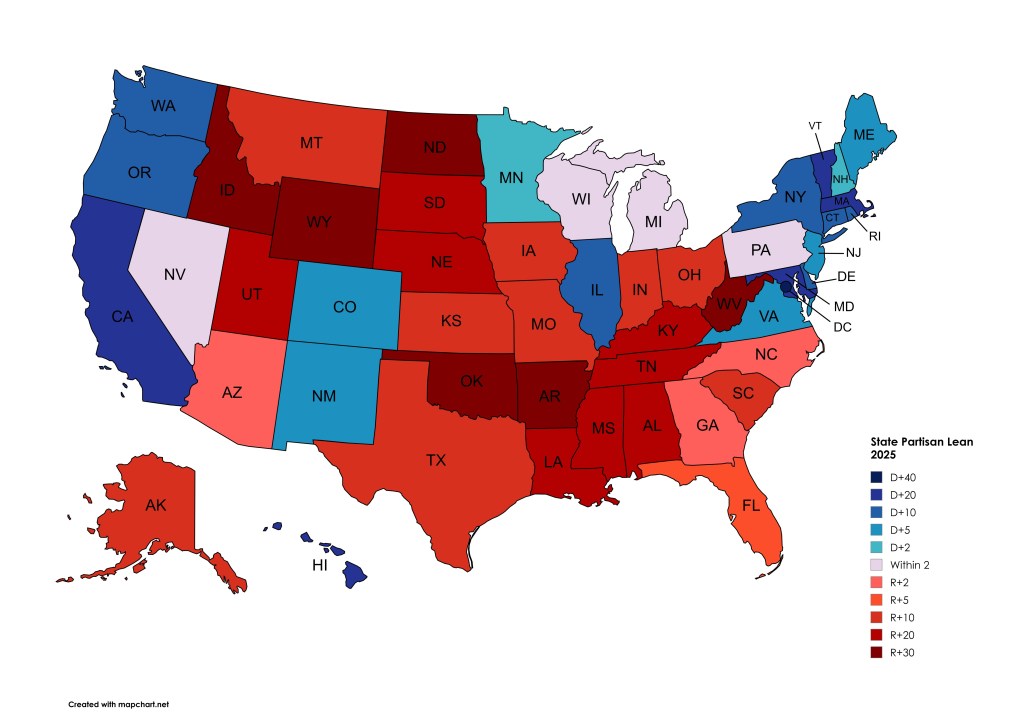

To estimate the partisan lean of each state, I calculate 3W-RDM, a weighted average of how much more or less Democratic than the nation a state voted in the three most recent presidential elections. This value is the expected state-level margin (Democratic % – Republican %) if the two major-party nominees tie in the national popular vote. The sum of 3W-RDM and the national popular vote has differed (in either direction) from the actual state-level result by an average 4.8 points over the last three elections, albeit only by 3.0 points in 2024. The standard deviation is 4.0, meaning the estimate is within 8.0 points of the actual value 95% of the time.

Figure 1 and Table 2 show current 3W-RDM for every state. Table 2 also lists 3W-RDM using data from 1984-92 and 2012-20 for historical context.

Figure 1: Current State Partisan Lean, Based Upon 2012-20 Presidential Voting

Table 2: Current and Historic State Partisan Lean (3W-RDM), Sorted Most- to Least-Democratic, 2025

| State | 2024 EV | 1984-92 | 2012-20 | 2016-24 | Wtd. Ave. Change 1992-2024 |

| DC | 3 | 75.3 | 82.7 | 84.2 | 1.5 |

| Vermont | 3 | 6.6 | 28.9 | 30.9 | 2.5 |

| Maryland | 10 | 8.0 | 26.2 | 28.6 | 2.8 |

| Massachusetts | 11 | 14.2 | 26.1 | 27.2 | 1.2 |

| Hawaii | 4 | 9.8 | 29.0 | 25.6 | 0.8 |

| California | 54 | 5.6 | 24.9 | 23.7 | 2.2 |

| Washington | 12 | 6.9 | 13.7 | 17.0 | 1.8 |

| New York | 29 | 10.8 | 20.2 | 16.6 | -0.6 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 15.1 | 16.6 | 15.3 | -1.2 |

| Connecticut | 7 | 0.7 | 13.9 | 15.1 | 1.3 |

| Delaware | 3 | -0.5 | 12.8 | 14.1 | 1.1 |

| Oregon | 8 | 7.3 | 10.1 | 13.1 | 1.6 |

| Illinois | 19 | 7.1 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 0.2 |

| Colorado | 10 | -2.4 | 5.7 | 9.7 | 2.5 |

| New Jersey | 14 | -4.0 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 0.3 |

| New Mexico | 5 | 2.0 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 0.8 |

| Virginia | 13 | -10.4 | 3.9 | 6.0 | 2.4 |

| Maine | 4 | -0.5 | 4.5 | 5.9 | -0.2 |

| Minnesota | 10 | 11.0 | 1.8 | 3.6 | -0.3 |

| New Hampshire | 4 | -11.6 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Michigan | 16 | 0.7 | -0.7 | -0.9 | -1.0 |

| Wisconsin | 10 | 4.7 | -2.4 | -1.4 | -0.8 |

| Nevada | 6 | -8.5 | -0.5 | -1.5 | 0.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 19 | 5.3 | -2.3 | -1.7 | -0.9 |

| Georgia | 16 | -7.0 | -6.5 | -3.0 | 1.6 |

| North Carolina | 16 | -7.0 | -5.8 | -3.8 | 1.1 |

| Arizona | 11 | -10.9 | -6.1 | -4.2 | 1.1 |

| Florida | 30 | -10.7 | -5.5 | -8.9 | -1.0 |

| Ohio | 17 | -3.0 | -9.8 | -10.7 | -1.6 |

| Texas | 40 | -7.7 | -12.0 | -11.3 | 0.9 |

| Iowa | 6 | 8.0 | -9.8 | -12.0 | -2.8 |

| Alaska | 3 | -15.7 | -15.8 | -13.5 | 1.8 |

| South Carolina | 9 | -13.9 | -15.9 | -16.3 | -0.3 |

| Kansas | 6 | -9.8 | -21.3 | -17.4 | 0.7 |

| Missouri | 10 | 3.2 | -19.0 | -18.5 | -2.7 |

| Indiana | 11 | -10.9 | -19.6 | -19.1 | -1.0 |

| Montana | 4 | -1.6 | -20.8 | -19.9 | -1.3 |

| Mississippi | 6 | -12.6 | -19.7 | -21.0 | -1.0 |

| Utah | 6 | -26.2 | -27.6 | -21.4 | 2.8 |

| Louisiana | 8 | -2.0 | -22.3 | -21.6 | -2.1 |

| Nebraska | 5 | -19.7 | -25.1 | -21.9 | 0.8 |

| Tennessee | 11 | -3.0 | -27.2 | -28.0 | -3.1 |

| South Dakota | 3 | -5.5 | -29.6 | -29.4 | -2.5 |

| Alabama | 9 | -10.7 | -29.2 | -29.4 | -1.9 |

| Kentucky | 8 | -2.9 | -30.3 | -30.3 | -2.9 |

| Arkansas | 6 | 3.3 | -30.3 | -30.1 | -4.2 |

| Idaho | 4 | -20.3 | -34.8 | -34.8 | -0.8 |

| Oklahoma | 7 | -13.4 | -37.8 | -35.3 | -1.8 |

| North Dakota | 3 | -12.7 | -35.4 | -36.4 | -3.1 |

| West Virginia | 4 | 9.2 | -41.4 | -41.5 | -6.3 |

| Wyoming | 3 | -14.5 | -47.5 | -46.2 | -2.7 |

| AVERAGE | -1.3 | -5.1 | -4.4 | -0.3 |

The core Democratic areas are essentially where they have been for three decades: New England (average D+16.2; New Hampshire D+2.8), the Pacific Coast (D+19.9)[2], the mid-Atlantic minus Pennsylvania (D+26.6, D+15.0 minus DC). These 15 states and DC contain a total of 182 EV. Add Illinois (19 EV) and Minnesota (10) in the upper Midwest, and New Mexico (5) and Colorado (10) in the southwest, and there are 226 EV in states at least 2.8 points more Democratic than the nation. Maine’s 2nd Congressional District (“ME-2”) typically votes Republican, while Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District (“NE-2”) typically votes Democratic. This is the Democratic presidential baseline, 44 EV shy of 270 – and precisely what Harris-Walz won in 2024.

The core Republican areas are also mostly where they have been for 30 years: the Mountain West minus Colorado (R+27.1); the six states running south from North Dakota to Texas (R+25.3); the five states in the western half of the Deep South (R+26.0); the border states of Missouri, Kentucky and West Virginia (R+30.0); and the Midwestern states of Iowa, Indiana and Ohio (R+13.9). Add the southern Atlantic states of South Carolina (R+16.3) and Florida (R+8.9), and the 24 states at least 8.0 points more Republican than the nation total 219 EV. Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina, while trending more Democratic over time, average 3.7 points more Republican than the nation. Giving their combined 47 EV to the GOP gives them a tied popular-vote base of 266 EV. Replacing the EV in NE-2 with the one in ME-2, and Republicans start a dead-even national election with 266 EV, four shy of victory.

As has been the case for more than a decade, a close national election would be decided by the combined 50 EV in Michigan (R+0.9), Wisconsin (R+1.4), Nevada (R+1.5) and Pennsylvania (R+1.7) – albeit with the 14 EV votes of Minnesota and New Hampshire in play for the GOP and the 43 EV of Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina in play for the Democrats.

Put another way, the Republicans have an edge in the Electoral College. Ordinary least squares (“OLS”) regressions of EV on national popular vote margin, using data from the last 19 presidential elections (1952-2024), show that in a tied national election, Republicans would win the EC on average by 284-251, with three EV going to third-party tickets and/or faithless electors.

Democrats: Electoral Votes = 1232.8*Popular Vote Margin + 250.61

Republicans: Electoral Votes = 1229.1*Popular Vote Margin + 283.62

This is something like Republicans winning the 266 EV from every R>3.0 state plus the 19 EV in Pennsylvania, or 285 EV. Democrats then win their 226 EV plus Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada, or 253 EV. This is also very close to the averages for the three consecutive presidential elections with Trump as the Republican nominee: Democrats 255, GOP 283, despite Democrats winning the popular vote by an average 1.7 points. Indeed, Democrats need to win nationally by 1.6 points to be roughly even money to win 270 EV, while Republicans could lose nationally by 1.1 points and be even money to win. For that matter, Republicans could theoretically lose the national popular vote by 1.6 points and still win 285 EV, following a recount in razor-thin Pennsylvania.

Despite this imbalance, though, Democrats have won the EC in five of the last nine presidential elections by winning the national popular vote by large enough margins. The 3.2-point average winning margin in these nine elections translates to an estimated 290 EV: winning their core 226 plus Michigan, Nevada, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania (278 EV total) and one of Georgia, North Carolina or Arizona. Still, the imbalance has been getting worse over time. In the mid-1990s, the average state was only 1.3 points more Republican than the nation, far lower than the roughly 4.7 points of the Trump elections.

So, what changed?

Relative state partisanship.

Figure 2: Weighted-Average Change in State Partisan Lean Since 1984-92

Figure 2 shows weighted-average change in 3W-RDM since 1984-92.[3] [Eds. Note: I used the unweighted average in the original version of this essay. The two values are correlated 0.92.] Only six states are essentially unchanged in their relative partisanship since the mid-90s: Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey and South Carolina. Overall, however, states shifted an average 3.1 points more Republican, relative to the nation. The variance between states also widened, with the standard deviation increasing from 14.4 to 23.4. Finally, in the mid-1990s, states that were at least 3.5 points more partisan averaged D+12.8 and R+12.0; today, those values are D+19.3 (222 EV) and R+22.4 (246 EV). In other words, over the last 30 years Republican states increased in partisanship by 3.9 points more than Democratic states.

The biggest pro-Democratic shifts over 30 years occurred primarily in four regions: the south Atlantic coast states of Maryland (+2.8), Virginia (+2.4), Georgia (+1.6), DC (+1.5) Delaware and North Carolina (+1.1); the southwestern states of Utah (+2.8), Colorado (+2.5), Arizona (+1.1), Texas (+0.9) and New Mexico (+0.8); the Pacific Coast states of California (+2.2), Alaska and Oregon (+1.8), Washington (+1.6) and Hawaii (+0.8); and the New England states of Vermont (+2.5), Connecticut (+1.3), Massachusetts (+1.2) and New Hampshire (+0.9). These 19 states plus the Plains Midwest states of Kansas and Nebraska shifted an average of 1.6 points more Democratic, relative to the nation, over the last three decades.

Two blocks of Republican states shifted the most Republican, relative to the nation, during this period. The first block, averaging 2.0 points more Republican (2.8 unweighted), is the “interior Northwest”: Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas. The second block, averaging 3.2 points more Republican over time, sit in a “Border/Central” region: Oklahoma, Louisiana, Missouri, Iowa, Kentucky, Arkansas, Tennessee, Arkansas and, most extremely, West Virginia. West Virginia is almost in a category by itself. Following the 1992 presidential election, when Bill Clinton and Al Gore won it by 13.0 points, it has become 6.3 points more Republican; Trump-Vance won it in 2024 by 41.0 points, a 54.0-point pro-Republican shift! Five states – Kentucky, North Dakota, Tennessee, Arkansas and West Virginia – shifted more Republican since 1993 than any state shifted Democratic, with an average Republican move of 3.9 points.

The Rust Belt shifted slightly more Republican since 1993, giving the GOP its current Electoral College edge. Moving west to east: Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York shifted a mean 1.0 points toward the GOP, relative to the nation. The other states to shift at least 0.5 points more Republican over the last three decades are the southern states of Alabama, Florida and Mississippi – and the deep blue state of Rhode Island. These 23 states shifted 2.0 points towards the GOP on average.

As for why states shifted strongly Democratic or Republican, I first wrote here about the growing partisan divide between white voters with (Democratic) or without (Republican) a college degree. Other explanations include self-sorting by geography (Democrats to the coasts and cities, Republicans to “flyover” country) and information (Democrats from traditional media, CNN and MSNBC; Republicans from right-wing media and Fox News).

**********

Looking beyond presidential elections, Table 3 lists the percentages of United States Senators (“Senators”), Governors and House Members who are Democrats in the D>5.0 (“Core Democratic”), Swing and R>5.0 (“Core Republican”) states. Data on the partisan split of each House delegation after the 2024 elections may be found here.

Table 3: Democratic Percentage of Senators, Governors and House Members in Three Groups of States

| Group | Senators | Governors | House Members |

| Core Democratic (n=17) | 97.1%* | 88.2% | 80.0% |

| Swing (n=9) | 77.8% | 66.7% | 40.4% |

| Core Republican (n=24) | 0.0% | 8.3% | 22.8% |

* Includes two Independents, Angus King of Maine and Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who caucus with Democrats.

These percentages tell an elegant story: states that are typically Democratic at the presidential level generally elect Democrats to statewide office, while states that are Republican at the presidential level generally elect Republicans to statewide office. Only three of 51 (5.9%) Democratic-state Senators and Governors are Republicans: Senator Susan Collins of Maine, and Governors Phil Scott of Vermont and Glenn Youngkin of Virginia. And only two of 72 (2.8%) Republican-state Senators and Governors are Democrats: Governors Laura Kelly of Kansas and Andy Beshear of Kentucky. Thus, only five of 123 (4.1%) Senators and Governors from the 41 most partisan states are from the “opposition” party. Democrats, though, overperform in the nine Swing states, holding 14 of 18 Senate seats and six of nine governor’s mansions, or 74.1%.

The House percentages are a bit murkier, reflecting Republican pockets in core Democratic states and Democratic pockets in core Republican states. Still, roughly 4/5 of House Members from these 41 states “match” their state’s partisan lean. Republicans slightly overperform in the Swing states, holding nearly 60% of the 89 House seats.

Pick your cliché. “All politics is local.” Not any more, as elections become increasingly nationalized. “I vote the person, not the party.” No longer true, given how closely voting for president/vice president, Senate, governor and House track. “Vote the bums out.” Well, voters seem to prefer bums from their party to anyone from the other party. As I noted regarding gerrymandering, this increasing partisan divide may be far more damaging for our two-party democracy than for either political party.

Until next time…and if you like what you read here, please consider making a donation. Thank you!

[1] These margin changes did not affect the winner in these states, as the Democrats still easily won California, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York, as did the Republicans Florida and Texas.

[2] With Alaska – trending less Republican over time – the average is D+13.2

[3] 1993 to 1997 = 1, 1997 to 2001 =2, etc.

3 thoughts on “The Not-So-Changing Geography of U.S Elections, 2025 edition”