This is one of the most iconic photographs in American history.

Easy as it is now to mock the editors of the Chicago Tribune for jumping the gun on the 1948 presidential election, they were merely anticipating what Americans thought was going to happen: incumbent Democratic president Harry S Truman (who had become president in April 1945 after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt) would be soundly defeated by the Republican nominee, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey.

As Zachary Karabell wrote in The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election:

“There was a full month left, and every informed observer believed that it was already over. Not even bookies would take bets on Dewey. But the candidates couldn’t just quit. Dewey couldn’t simply retreat to his Pawling farm and wait for the inevitable, and Truman wasn’t about to get off his train and concede defeat. They may have been going through the motions, but the motions were important. It was imperative that each of them play his part, if not to perfection, then at least convincingly. Because for all the prognostications, the election lay weeks in the future and the future might hold surprises.”[1]

Further, having “decided that the outcome was sealed, reporters and commentators ignored signs that might have pointed in a different direction.”[2] Despite the fact that the three major pollsters—Gallup, Roper and Crossley—had shown Truman gaining in mid-October polls[3], no poll was conducted in the final two weeks of the campaign[4].

An average of these final, mid-October polls showed Dewey ahead 50.8 to 42.5, with the remaining 6.7% split between the two main independent candidates (State’s Rights [aka Dixiecrat] J. Strom Thurmond and Progressive Henry A. Wallace), other third-party candidates and undecided voters. Two months earlier, Truman had been polling around 34%, so he had gained some 8.5 percentage points, while Dewey had been polling around 47.5%, so he had gained about 3.3 percentage points[5]. Truman was clearly netting voters…but nobody thought it would be enough.[6]

Dewey and his advisors on the “Victory Express”—Truman was not the only candidate with a campaign train—saw the tightening polls. However, they chose to continue their “dignified, sincere, and clean” strategy of projecting a “noble mien.”[7] And while it is a myth that Dewey sat back and waited for the electoral verdict (he had traveled 16,000 miles to Truman’s 22,000 miles[8]), he had not campaigned with nearly the same zeal or urgency as Truman (or Thurmond or Wallace, for that matter).

One Cassandra did try to shake the Dewey campaign out of its complacency. Edward Hutton (of E. F. Hutton) sent a telegram to the Dewey campaign nine days before the election “warning that contrary to all the polls and pundits, defeat was in the air unless Dewey showed some hints of the toughness he once exuded as a prosecutor.”[9]

Hutton was prescient.

On November 3, 1948, Truman won 49.6% of the popular vote, Dewey won 45.1%, and Thurmond and Wallace each won 2.4%, with the remaining 0.6% divided among a variety of third-party candidates and write-in votes. Overall, Truman beat Dewey by just over 2.1 million votes. The 531 Electoral College votes (EV) were divided thus: Truman 303 (28 states), Dewey 189 (16), Thurmond 39 (Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina).

Dewey had fallen just 77 EV short of the 266 he needed to win. Had he won about 18,000 more votes in California (47.6-47.1%), 34,000 in Illinois (50.1-49.2%) and 8,000 (49.5-49.2%) in Ohio, he and his running mate, California Governor Earl Warren, would have won the 1948 presidential election, saving the Chicago Tribune decades of embarrassment.

**********

Inspired by Cody Franklin and his entertainingly inventive website AlternativeHistoryHub, I conducted a thought experiment:

What if Dewey had won California, Illinois and Ohio in 1948, and he, not Truman, had been sworn in as president of the United States on January 20, 1949.

My answers—which are purely speculative, obviously—surprised me.

First, though, let us consider how Dewey could have won.

The simplest way would have been for Dewey, once the polls began tightening in early October, to heed Hutton’s warning. A more aggressive stance against Truman (more on this later) would have been catnip to a bored press corps, who in turn would have eagerly written stories about how the “exciting” and “engaged” Dewey was taking nothing for granted and battling to the very end. This, in turn, would have caught the attention of a sleepy electorate…and, in this scenario, just enough of them vote for Dewey, rather than Truman, in California, Illinois and Ohio (and perhaps Idaho, Iowa, Nevada and Wisconsin—all decided by <5 percentage points) to give Dewey a narrow Electoral College victory.

The thing is, even if Dewey had won all seven of these states (giving him 23 to Truman’s 21), he would almost certainly still have lost the popular vote by more than 1 million votes, becoming the third Republican president to win an Electoral College majority while losing the popular vote.

Moreover, in this counterfactual universe, the Democrats still likely recapture the United States House of Representatives (House) and Senate (Senate), though perhaps not by 92 and 12 seats, respectively.

At the same time, however, the Democratic Party itself would have been severely fractured, having lost its first presidential election in 20 years. Truman’s victory is even more astonishing when you consider that two former Democrats—Thurmond, the segregationist governor of South Carolina, and Wallace, Roosevelt’s populist Vice President (1941-45)—had run against him form the right and left, respectively.

On July 14, 1948—towards the end of the Democratic National Convention that would nominate Truman and Kentucky Senator Alben Barkley for president and vice president—Minneapolis Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey gave a rousing speech in favor of a strong civil rights plank (“I say the time has come to walk out of the shadow of states’ rights and into the sunlight of human rights!”). This led the Alabama and Mississippi delegations to leave the Philadelphia convention hall in protest. Meeting in Birmingham, Alabama on July 17, what became the State’s Rights Party (which saw itself as the true representatives of southern Democrats) nominated Thurmond and Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright for president and vice president.

Wallace, meanwhile, had broken with Truman on September 12, 1946. That day, then-Commerce-Secretary Wallace gave a speech in New York City’s Madison Square Garden (which he always insisted had been approved by Truman) in which he outlined a far more accommodating view toward the Soviet Union (seeing the two nations as morally equivalent within their spheres of influence) than the political establishments of either party. He also called for the newly-formed United Nations (UN) to control all atomic weapons. Truman, pressured by Secretary of State James Byrnes, asked for—and received—Wallace’s resignation. Less than two years later, on July 23, 1948, the Progressive Party would meet in Philadelphia and nominate Wallace and Idaho Senator Glen H. Taylor for president and vice president.

It is noteworthy here that Truman, as he fought to win reelection, sounded more and more like a liberal populist in the last month of the campaign.[10]

In sum, then, the political bottom line is this:

After being expected to win easily, President Dewey would only have eked out a narrow Electoral College victory while losing the popular vote by 2-3 percentage points. And while the Democratic Party may have been fracturing, it would still have solidly controlled both the House and Senate, though in this alternate world, more Republican House and Senate candidates win outside the South (where the Republican Party effectively did not exist), making southern Democrats an outright majority of Democrats in both the House and Senate. [11].

And here is where I make my first prediction.

Dewey and Warren were both moderate governors who had campaigned in platitudes of unity more than specific policy proposals. They also had zero foreign policy experience.

Dewey’s choice of Secretary of State would thus have been vitally important. And I believe that the obvious choice would have been General Dwight David Eisenhower.

Anti-Truman Democrats had tried to convince the popular World War II hero to accept the Democratic nomination, while Dewey worried about his entry into the Republican nominating contest right up until the July conventions, when Eisenhower unequivocally announced he would not accept either party’s nomination.[12]

But Eisenhower still loomed on the horizon for 1952, and Dewey could have eliminated that threat by naming Eisenhower his Secretary of State. Despite having just become president of Columbia University, I cannot see the long-time military man Eisenhower (who we now know was a Republican) refusing a direct request from a president-elect.

I also suspect that the practical Dewey, who by all account built quality staffs throughout his career, would have had a fairly bipartisan and non-ideological Cabinet.

Meanwhile, it would have been Dewey and Eisenhower (not Truman and George C. Marshall, Secretary of State since January 1947) who would have faced these immediate foreign policy crises:

–August 29, 1949: The Soviet Union successfully tests its own atomic bomb. Does a President Dewey order the creation of the hydrogen bomb, as President Truman did?

–October 1, 1949: Mao Zedong proclaims the People’s Republic of China, creating a second Communist superpower. The accusation (fair or not) that Truman “lost” China, and was thus not tough enough on Communism, would instead have been hurled at the inexperienced Dewey, though mitigated by the stature of Eisenhower (and the fact that Dewey could still point back to Truman).

–June 25, 1950: 75,000 soldiers from the North Korean People’s Army cross into the American-backed Republic of Korea, in what has been described as the first military action of the Cold War. Does President Dewey order American troops to the Korean peninsula in July 1950, making what could have been “just” a civil war into a proxy war between the United States (and its allies) and the Soviet Union (and its allies)?

Given the emerging bipartisan consensus that Communism was an international threat that needed to be contained, combined with Dewey’s and Warren’s own lack of foreign policy experience and the internationalist slant of the 1948 Republican Party platform[13], my best guess is that our foreign policy would have changed little. If pressed, I would argue Dewey also orders more advanced nuclear weapons. However, I think the responses to Mao and the invasion of South Korea would have been more muted; it is just possible not as many troops are sent to Korea and an armistice is achieved much sooner. After all, it only took President Eisenhower six months to achieve the armistice which still holds.

Of course, this means that there would have been no dramatic firing of General Douglas MacArthur on April 11, 1951, after he openly bucked President Truman on whether to bomb and invade China.

**********

As important as those crises were, I think the most profound change would have been no McCarthyism (at least, not then).

On February 9, 1950, first-term Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin gave a speech in Wheeling, WV during which he waved what he claimed was a list of 205 Communists, known to Secretary of State Marshall, who had infiltrated the State Department.[14] That he was ultimately unable to name a single one did not prevent the rise of McCarthyism, a tactic of using unsubstantiated claims of Communist sympathy (or other scurrilous description) to defame reputations.

While an emboldened McCarthy, as chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations (and its permanent subcommittee on investigations), eventually took on President Eisenhower (and lost), I have a difficult time seeing McCarthy challenging a State Department run by Eisenhower in February 1950.

It is also just possible that the McCarran Internal Security Act, requiring the registration of “Communist” agencies with the United States Attorney General, never passes (over Truman’s veto!), though that is merely speculation on my part.

That is foreign and national security policy. What about domestic policy?

**********

Before I answer that question, just bear with me while I briefly review the life of the man Alice Roosevelt Longworth once (wrongly) derided as “the little man on top of the wedding cake.”[15]

Thomas Edmund Dewey was born in Owosso, MI, on March 24, 1902. His father, George Martin Dewey, was editor of The Owosso Times and deeply involved in local Republican politics. After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1923, his first thought was to pursue a career in music; he had an excellent baritone. As a backup plan, he enrolled at Columbia Law School in September 1923, graduating in only two years.

After a stint in private practice, the 29-year-old Dewey was appointed chief assistant to George Medalie, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY). In 1933, after Dewey was himself appointed U.S. Attorney for SDNY after Medalie’s abrupt resignation, he secured the conviction of mobster Waxey Gordon (aka Irving Wechsler) for income tax evasion.

Two years later, he was appointed Special Prosecutor and charged with prosecuting such organized crime figures as Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Arthur Flegenheimer, aka Dutch Schultz.

Allegedly, Dewey’s investigations so unnerved Schultz he planned to have Dewey killed, going so far as to monitor the routine of the clockwork Dewey; Dewey took the threats in stride, refusing to alter his routine. However, rather than face the heat that would result from Dewey’s assassination, Luciano reportedly ordered contract killers from Murder, Inc. to kill Schultz. While dining with confederates in the Palace Chop House in Newark, NJ on the night of October 23, 1935, Schultz and his confederates were gunned down by unidentified men

[Side note 1: I love this reenactment of the death of Schultz from one of favorite “guilty pleasures, the entertaining {and historically inaccurate} The Cotton Club.]

[Side note 2: I cannot recommend highly enough Murder, Inc. but Burton Turkus and Sid Feder.

[Side note 3: Writing this, I wonder how history would have changed if Schultz actually had killed Dewey in 1935. But that is an entirely different post.]

Dewey would send Luciano and 71 other people to prison before easily being elected New York District Attorney in 1937; he served only one term. He first ran for governor of New York in 1938, losing narrowly to Democrat Herbert H. Lehman.

Still, this was enough for national Republicans to try to secure the presidential nomination for the 38-year-old Dewey, though he ultimately lost the nomination to Wendell Willkie (who in turn was soundly defeated by President Roosevelt).

In a 1942 rematch, Dewey beat Governor Lehman handily, ultimately serving three four-year terms as governor.

In 1944, Dewey was the Republican nominee for president, losing to President Roosevelt. Four years later, he would beat Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen and Ohio Senator Robert Taft (among others) for the Republican nomination…and that brings us back to the election of 1948.

**********

Two facts about Dewey’s pre-1948 career strike me as relevant.

One, when Dewey was appointed Special Prosecutor in 1935, he chose a black woman lawyer named Eunice Hunton Carter to be his deputy assistant; she was the only member of this 20-person staff who was not a white man. Carter was instrumental in the indictment and conviction of Luciano, as she organized a series of 200 raids on Luciano-run brothels, ultimately finding three women to testify against him.[16]

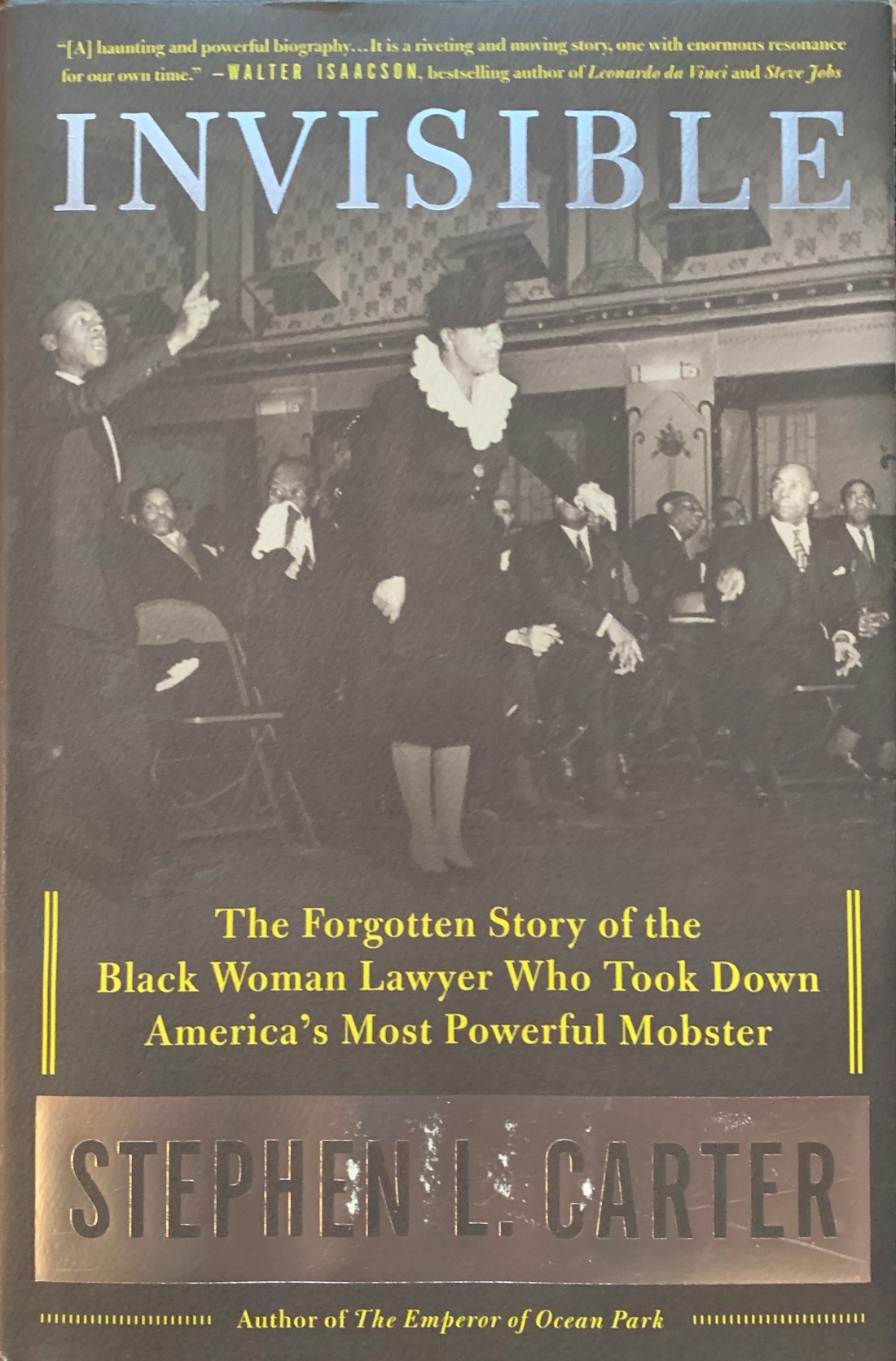

[UPDATE: In February 2019, I finally got around to using a gift certificate to The Concord Bookshop I had received for my birthday some 17 months earlier. I had a difficult time deciding until I alighted upon this:

It did not even occur to me until later that February is Black History Month.

Here is a key passage (pp. 106-07):

“In an interview four years later, Dewey himself told the story differently. In his version, his selection of Eunice [Hunton Carter] reflected less his determination to investigate Harlem[‘s numbers rackets] than his unprejudiced eye for talent:

“I hired Mrs. Carter the first day I met her. Shortly after I was appointed, a prominent judge, who knew that I was looking for a woman assistant, told me he knew a wonderful colored woman lawyer. I told him to send her over, was impressed, and retained her. She has made good, and commands the respect of the bench of the city.

“In applauding Eunice [Hunton Carter] for making good, Dewey here is of course actually applauding his own ability to spot talented people. Probably the skill is one he genuinely possessed. After all, his original twenty assistants included any number of future judges and superstar lawyers, as well as a man who would later serve in the cabinets of two Presidents of the United States, one as attorney general and the other as secretary of state.“]

Two, as governor of New York, Dewey appointed the first state commission to eliminate religious and racial discrimination in employment.

Couple these racially progressive actions with a) a 1948 Republican Party platform that, while otherwise “filled with vague promises and vapid language,”[17] did include a modest anti-racial-discrimination plank and b) a Democratic Party cracking between Northern liberals and Southern segregationists, and I propose the following.

Seeking to capitalize on Democratic Party divisions on race and finding himself hemmed in politically, President Dewey decides to take bold action on racial equality, effectively starting the Civil Rights movement as early as 1949. This single action, with the potential to lure black voters back to the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln after 16 years of voting for President Roosevelt, would have fundamentally altered American politics for decades.

Remember, for Dewey even to have won this narrow victory in 1948, he would had to have taken bold and assertive action in the last few weeks of the campaign. Perhaps he begins to highlight both his own actions and the anti-discrimination plank, putting Truman in a vice between the mistrusting liberals and the non-Dixiecrat southern Democrats.

It is equally possible (though far from certain) that the moderate (even liberal, other than on the death penalty) Dewey would have built a coalition of Northern Democrats and like-minded Republicans to advance more liberal policies, in much the same way President Ronald Reagan built a “conservative coalition” of Republicans and Southern Democrats in the early 1980s. This would have resembled President Richard Nixon’s first term, where he essentially ceded domestic policy to Congressional Democrats to focus on foreign policy.

**********

The cyclical nature of American politics suggests that, rather than losing 28 House and five Senate seats in the 1950 midterm elections, Democrats would have gained seats instead. And since the southern Congressional delegation was already uniformly Democratic, these newly-elected Democrats would almost certainly have been Northern Democrats who had run against the Dewey Administration from the left. This, in turn, could easily have led to a three-way split in Congress between Northern Democrats (led by now-Senator Humphrey?), centrists of both parties (led perhaps by Senator Lyndon Johnson of Texas, who would become Democratic leader in 1953), and southern Democrats (who perhaps start to align with more conservative Republicans on overtly racial and virulently anti-Communist lines).

Assuming Dewey and Warren were renominated in 1952, they would have faced a Democratic Party continuing to split along geographic lines; Thurmond may well have run again, this time luring more key southern Democrats (e.g., Senator Richard Russell of Georgia) to support him.[18]

Russell, Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee and New York governor Averell Harriman actually were Illinois Governor Adlai E. Stevenson’s chief competition for the Democratic nominee for president in 1952. In the alternate universe of a President Dewey, it is possible that Harriman wages a stronger battle for convention delegates and defeats him. Or that Kefauver (the early balloting leader) formally breaks with the Southern Democrats and wrests the nomination.

Let’s say Stevenson and Kefauver are the presidential and vice-presidential nominees, in some order. In a universe where four or more nominally Democratic southern states vote for Thurmond, it is hard to see how Stevenson-Kefauver[19] (or vice versa) beats Dewey-Warren.

And here is where history really would have taken a left turn.

**********

On September 8, 1953, Chief Justice Fred Vinson (nominated by Truman in 1946) died.

In actuality, President Eisenhower, then in his first term, successfully nominated former California governor and 1948 vice-presidential nominee Earl Warren to be Chief Justice. The Warren Court had a profound impact on American life, most notably through the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954. This case overturned the precedent set six decades earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson, finding that “separate can never be equal.”

Warren knew the outcome of this case was going to be controversial, so he sought—and obtained—a unanimous 9-0 decision.

The Warren Court also handed down key decisions on legislative apportionment (Reynolds v. Sims), marriage (Loving v. Virginia), contraception (Griswold v. Connecticut) and criminal justice (Mapp v. Ohio, Miranda v. Arizona).

I have no idea who a President Dewey would have nominated to replace Chief Justice Vinson. But it is hard to imagine a different Chief Justice having the same impact on American life as Earl Warren did.

Simply put, if Thomas Dewey had won the presidency in 1948 and in 1952, there is almost certainly no Chief Justice Earl Warren. And with no Warren Court, it could well have taken years longer to desegregate the nation’s schools, codify the notion of “one person, one vote,” decriminalize interracial marriage and contraception, put reasonable limits on the seizure of evidence, and require all arrested persons to be properly and quickly informed of their Constitutional rights.

Instead, in this alternate universe, we are considering the possibility of the 65-year-old Warren himself seeking the Republican presidential nomination in 1956 (as he had in 1948). Had he run, it is not clear who else could have won the nomination. For example, it is unlikely that Nixon would have challenged a sitting Vice President from his own state rather than seek reelection to a second term.

An intriguing possibility is New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. In this alternate timeline, he runs for governor in 1950, rather in 1954. Or perhaps a first-term Senator from Arizona named Barry Goldwater would not have waited until 1964 to run for president (unless the realignment into the liberal Republican and conservative Democratic Parties had already begun, and Goldwater conservatives were joining the Democrats, while liberal Democrats were joining the Republicans).

And then there is the 66-year-old Eisenhower. The fact that he almost did not run for reelection in 1956 because of his health likely takes him out of contention.

So let us assume Warren is Republican nominee for president in 1956, perhaps with a border-state Democrat as his running mate. Or even Rockefeller himself.

Who would he have faced?

If the Democratic Party has healed its divisions, than the nomination battle in 1956 would have been a free-for-all between Stevenson, Kefauver, Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, Humphrey and (perhaps) Johnson—much like 1960 actually was, but four years earlier.

For some reason, a Kefauver-Kennedy ticket jumps out at me. The difficulty sitting Vice Presidents have had recently in winning the presidency in their own right implies the Democrats would have been modest favorites to win.

That said, if the southern Democrats had formed their own party by now, perhaps luring conservative Republicans, then Warren-Rockefeller could have won a three-way race with Kefauver-Kennedy and, say, Russell-Goldwater.

Who knows?

Beyond that, however, I dare not speculate…though I am curious what you think.

Well…one final thought. What so fascinates me about the 1948 presidential election is that while Harry Truman is my favorite president, the more I learn about Tom Dewey, particularly his prosecutorial efforts in the mid-1930s, the more intrigued I am. Love Truman though I do, I think Dewey would have been a solid president, not dissimilar to Eisenhower or the underrated first George Bush. I also do not want the hard-working Dewey to be nothing more than the guy who did NOT defeat Truman. He deserves more than that.

Until next time…please wear a mask as necessary to protect yourself and others – and if you not already done so, get vaccinated against COVID-19! And if you like what you read on this website, please consider making a donation. Thank you.

[1] Karabell, Zachary. 2000. The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. pg. 241.

[2] Ibid., pg. 242.

[3] Ibid., pg. 249.

[4] http://www.zetterberg.org/Lectures/l041115.htm

[5] Karabell, pg. 186.

[6] The enormity of the polling error was assessed by a post-election commission led by Harvard statistics Professor Frederick Mosteller. It concluded that by not conducting polls through Election Day, they missed a continued shift to Truman. Moreover, their use of quota sampling (as opposed to truly random sampling), a misunderstanding of how undecided voters would break and an inability to determine just who would vote made their samples (and resulting projections) statistically biased toward Dewey.

[7] Ibid., pg.250.

[8] Ibid., pg.252.

[9] Ibid., pg.250.

[10] Ibid., pp. 245-46.

[11] I define “Southern” as Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. In the timeline that actually occurred, southern Democrats occupied 118 (44.9%) of the 263 Democratic House seats and 26 (48.1%) of the 54 Democratic Senate seats.

[12] Karabell, pg. 152-53.

[13] Ibid., pp. 146.

[14] “U.S.Office Still Under Red Charge,” Lansing State Journal (Lansing, MI), February 11, 1950, pg. 1.

[15] I base this account on Dewey’s New York Times obituary. See also Karabell, pg. 77.

[16] To be fair, there is controversy around this testimony, as laid out in Ellen Poulson’s 2007 book The Case Against Lucky Luciano: New York’s Most Sensational Vice Trial.

[17] Karabell, pg. 146. See also pp. 147 and 154-57.

[18] However, given the United States constant reversion to the two-party system, it is likely that the end result is something very much like the two parties we have today: a left-of-center Democratic Party strongest in cities, college towns, the Pacific Coast, the mid-Atlantic and New England; and a right-of-center Republican Party strongest in rural areas and small towns, the South, the Plains Midwest and the upper Mountain West.

[19] Which actually was the Democratic presidential ticket in 1956. On a floor vote called by Stevenson, Kefauver edged a young Massachusetts Senator named John Fitzgerald Kennedy to win the vice-presidential nomination.

8 thoughts on “What if Dewey HAD defeated Truman…”