One night in April 1984, I drove three friends across the Delaware River into Trenton, NJ. There, we ate a meal at Pat’s Diner. I tell a version of this pivotal story in Chapter 10 of my INTERROGATING MEMORY book. I plan to write a longer version soon.

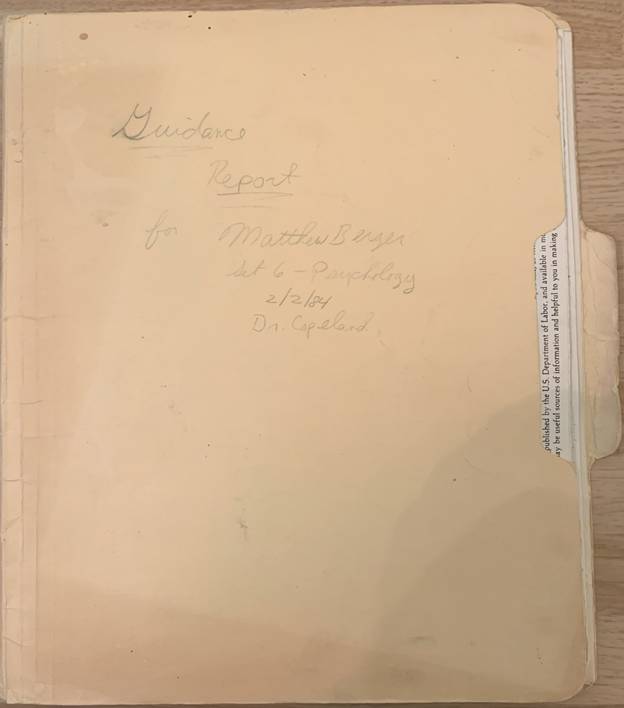

To prepare to write this story, I pulled a thick manila folder with a sticky note affixed reading “1984” from my filing cabinet. Within that folder was another folder on which I had penciled “Guidance Report for Matthew Berger Set 6 – Psychology 2/2/84 Dr. Copeland” in cursive. The words are fading, but you can still see that “Guidance Report” is double underlined.

This folder dates to the last semester I spent at Harriton High School in Rosemont, PA, a Philadelphia suburb. Doctor Theodore “Doc” Copeland, who also taught geometry, had taught psychology to seniors for more than three decades. According to the lead story in the June 1984 Harriton Free Forum,[1] which I served as co-News-Editor, a newly-discovered gap in Doc’s certification meant he would not teach psychology the following year, despite having a doctorate in the field.

Students in the course completed a battery of personality and aptitude tests. In September 1983, I completed the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (“SCII”) and the Personal Style Inventory (“PSI”). The SCII uses responses to 325 questions to calculate similarity to the profiles of persons in 99 occupations, divided into six themes: Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, Conventional. I scored moderately high on Artistic and Enterprising, very low on Realistic and average otherwise. Drilling down further, I most closely matched the profiles for Office Practices (high), and Mathematics and Writing (very high), while I was the furthest from Medical Service (low), and Agriculture, Athletics, Mechanical Activities, Medical Science, Military Activities and Nature (very low). That I later found refuge in a website devoted to data-driven essays speaks to the validity of this assessment.[2]

The SCII also denoted me 60 on Academic Comfort and 41 on Introversion/Extroversion. The former score aligns with earning a PhD, which I did in 2015 (epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health), while the latter is just outside the extroverted range. By contrast, the PSI denoted me a pure ambivert, scoring 20 on introversion and extroversion. It also denoted me narrowly more intuitive (23) than sensing, judging (22) than perceiving, and thinking (21) than feeling. Shades rather than extremes.

Three years earlier, at the end of 1980,[3] I completed the Differential Aptitude Tests (“DAT”). The DAT printout sits in my Guidance Report folder. Based on my responses, I scored in the 97th percentile or higher on Verbal Reasoning, Numerical Ability, Abstract Reasoning and Spelling, as well as on Clerical Speed and Accuracy, and Language (both 99th). Space Relations (75th) and Mechanical Reasoning (45th) were the outliers. These percentiles matched my top career goals of Social Sciences, Math and Physical Science Research, and Literary and Legal. Through June 1995, when I resigned from the doctoral program in government at Harvard, I planned to become a political scientist.

We returned to the test batteries in January 1984, after which I typed a 10-page “Guidance Report” I wrote about myself in the third person. The page length and a plethora of careless typing errors (so much for Clerical Accuracy) knocked my grade down to a B+. This report combined the earlier assessments with self-reported General Information, Family Background, Educational Background, Cocurricular Activities, Work and/or Travel Experience, Hobbies and Interests plus four new assessments: California Psychological Inventory (“CPI”), Life Goals Profile, Philosophy of Life and the Communication Skill Scale. The latter required both a self-assessment and an assessment by someone “with whom you have frequently communicated over an extended period of time.” I do not recall who it was, but s/he scored me an average 0.5 more positively on 10 items, scaled 1-5, than I scored myself. The largest differences – 3 (me) vs. 5 (partner) – were for “Capacity to hear, evaluate and respond positively to CRITICISM AND NEGATIVE FEELINGS from others” and “CLARITY in expressing oneself.” The only item on which my partner scored me lower (3) than I did (4) was “Capacity to hear, evaluate, and respond positively to PRAISE AND POSITIVE FEELINGS FROM OTHERS.” As a Writer, I strive for clarity and to respond well to both criticism and praise. These things are not always easy to do.

Overall, there are few surprises here. The Guidance Report reminded me how busy I was at the end of high school, beyond the Free Forum and the Math Team, which I served as Secretary and President in successive years. My philosophy of life, which I admitted I had never given much thought, is all over the place. I just want to be happy, and I am a contented fatalist, but I also take full responsibility for my actions, seeking to effect change whenever I can. As with the PSI, there is evidence of cognitive and emotional duality both here and on my Life Goals Profile. I am a doer and joiner who cares far more about mental health than prestige or power. I note here I had attempted suicide a second time a year earlier then barely participated in some slapdash psychotherapy, while it took me another 32 years to acknowledge and treat my clinical depression. Still, I also highly valued good friends and mature love. Happily, I have always had the former, while the latter took some time.

Which brings me, unfortunately, to the CPI.

**********

Over two consecutive weekends early in December 1979, I took the est training at a hotel in the Society Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia. I had just turned 13, the minimum age to take the standard (adult) training with parental approval. Whatever your feelings on est, its basic message – there are no magic solutions to your problems, only the hard work of conscious personal responsibility – still resonates with me. A key component of what I dubbed “interrogating memory” is a deep and sincere intellectual humility, a willingness to be proven wrong about something we are convinced we know. This happened many times as I researched and wrote INTERROGATING MEMORY.

As a side note, around 2019, when I was still on Twitter, and it was still called Twitter, somebody insisted the AK-47 automatic weapon was so named because it had been developed in Alaska, often abbreviated AK, the 47th state to enter the Union. When I responded that Alaska became the 49th state on January 3, 1959, I was met with bizarre and furious pushback, an insistence that no matter how many sources I cited, this person will maintain Alaska was the 47th state. I quickly stopped arguing, realizing that the very act of trying to convince this person was itself the problem. Not being trained in psychology, I will not attempt to explain this need to cling to demonstrably false facts.

In December 1979, meanwhile, my mother and I lived with her sister and her two young children in the Philadelphia suburb of Bala Cynwyd (pronounced kin-wood). My mother was very happy to spend $300 ($1,321 today) she barely had for me to take the est training, but she was disinclined to drive me roughly 40 minutes roundtrip twice a day on consecutive Saturdays and Sundays. On the Thursday night before the first Saturday, however, I attended a pre-training seminar. There, I asked for a regular ride, and was offered one by a pleasant young man in his late 20s or early 30s.

We talked a lot on these drives – I was a prolific talker once I got started, and I had a great rapport with adults. At the time, I wanted to pursue archaeology as a career, intending to attend the University of Pennsylvania. The ruins of Chichén Itzá, on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, held a particular fascination for me, though I do not recall why. Great, announced my driving companion, we shall go there together sometime after the training ends. Just the two of us.

It is perfectly plausible this single young man felt a genuine kinship with me and wanted to travel with me to a foreign country – no more, no less. When you are immersed in the est training and, especially, once you complete it, you feel euphorically empowered to do anything. He always behaved appropriately around me, and I never felt unsafe with him. He was smart and kind, and I liked him.

My mother, however, vetoed this trip faster than a cheetah on speed. Her primary argument was, “I don’t care who you are, you are not taking my minor child out of the country without another trusted adult.” This was a wise choice in retrospect, and while I felt a momentary pang of disappointment, I ultimately agreed. But I have reason to believe my mother was also responding to the homophobic stereotype of “gay men are predators toward younger boys.”

Now, I have no idea what this man’s sexual orientation was, nor what was in his mind when he suggested he take me to Yucatan. I had only just begun to explore my own sexuality, let alone be aware of anybody else’s. One year earlier, I happened to look to my right in the rear of a movie theatre, just before the 1952 version of Scrooge began. A female blonde classmate stood up and, as I write in Chapter 9 of INTERROGATING MEMORY, “…it was as though every hormonal switch in my 12-year-old body flicked on, all at the same time, and with 11-level intensity.”

Flash forward to the fall of 1982.

A year earlier, in June 1981, I had attended a party at Ashbridge Park, about ½ mile south of Harriton High School and about 1 mile northwest of Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church. It was in the latter building that four sixth-grade girls had met. Now, at the end of 9th grade, two of the girls attended Harriton with me while the other two attended nearby Radnor High School. I talked to the latter two girls in a tree in Ashbridge Park, not realizing I was starting lifelong friendships. The following September they and a third girl co-hosted a “Hi, We Haven’t Forgotten You Exist” party. This was the first of a round robin of parties thrown by members of an inter-high-school group during my sophomore year. While I was deeply – and, for a time, mutually – attracted to one of the two Radnor girls, it was her friend who became my first serious girlfriend, following an ever-closer friendship. Now married to other people, we remain close.

At the end of the summer of 1982, my girlfriend boarded a plane for Spain. She spent the next year there as an exchange student, effectively ending our romance and the inter-high school group. One older student in our group, meanwhile, had just graduated from Radnor. His sister – one year younger than most of us – was also in the inter-high-school group. He was likely in our group because he a) had a car and b) worshipped at Bryn Mawr Presbyterian, where he earned money doing odd jobs. Over the summer, he and I had become closer friends.

One night, shortly after the start of my junior year at Harriton, he and I sat in his car in the parking lot of the WAWA convenience store on Belmont Avenue in Belmont Hills. My memory makes the car red. He was eating a kind of vanilla ice cream cone, and I noticed how large his lips seemed around the top of it. I was eating a Hostess cherry pie, possibly with a plastic bottle of Sprite.

I forget how the subject arose, but there and then he became the first person to come out to me. He admitted he was attracted to me while noting I had expressed a general openness to trying new things. Before I could respond to that, he added that he also realized that my preferences lay elsewhere, and he accepted that.

While I had never given his orientation any thought, I was not surprised he was gay. I probably said something brilliant like, “Really? That’s cool.” It made no difference to me one way or the other, though I was flattered he felt comfortable enough to reveal his orientation to me. I might also have asked if he had told anybody else. If so, I forget his response.

However.

When I told my mother what my friend had told me, it made a huge difference to her. He and I had spent time in my bedroom together, watching TV. My mother and I had moved to an apartment complex in the suburb of Penn Valley two months after my est training.

Even though he had never made a pass at me, nor had I ever felt uncomfortable with him, she no longer allowed me to bring him to my bedroom. She might have expressly forbade me from being friends with him, period – my memory is a bit fuzzy four decades later. Despite being a liberal in many respects, she shared her generation’s homophobia, accepting the insidious two-part myth that gay men preyed upon helpless boys, seeking to turn them gay. Her fearful reaction is why I conclude she assumed my est driver was a gay predator.

And here I make my first confession.

As much as I liked this friend, and after only a half-hearted protest, I did what my mother asked. Since I never recall going to his house, that effectively ended our friendship. I deeply regret not pushing back harder against my mother’s homophobia. I could say that I knew it was going to be me against nearly every adult in my life, and I was not yet equipped for that fight, but that does not change my (in)action.

As a side note, two other men in the group came out over the next 5-10 years. One was a mild surprise (mostly because of his staunch Catholicism), one was not.

To my mother’s credit, though, she evolved over the next few years. In the summer of 1986, I was an unpaid intern at the Brookings Institute in Washington, DC, renting an apartment in an Adams Morgan brownstone. The house’s owner was openly gay, and – perhaps because there were other straight residents in his house – my mother did not object. During my senior year at Yale, I had two gay male landlords who leased apartments in one house while living in the neighboring house. It barely even merited conversation. What might have happened in the interim is that one or both sons of a close family friend came out. These were young men she had known and loved for years, shifting her perspective.

**********

This brings us back to the CPI – and my second confession.

What I completed on January 9, 1984 was the 1956 version of the CPI. It consisted of 480 true-false questions which yielded percentiles along 18 dimensions – for some reason, Independence and Empathy are excluded from my profile sheet. Scores are plotted on a chart along with the male or female norms for high school and college students. My percentiles ranged between 50 (Sense of Well Being, Self-Control – effectively tied with college male norms) and 76 (Dominance, Self-Acceptance). Within four meta-categories, whose names have changed over time, my percentiles were highest (average = 68.5) on “poise, ascendancy, self-assurance and interpersonal adequacy.” Underneath this category on the profile sheet, I wrote “ambitious, verbally fluent, aggressive, persistent, co-operative, intelligent, efficient, well-organized, makes good impression.” I had the lowest average percentiles (57.3) – albeit higher than high school and college male norms – on “socialization, responsibility, intrapersonal values and character.”

One of the three categories in the meta-category “measures of intellectual modes and interest modes” is Femininity, sometimes listed as Femininity-Masculinity. I ranked in the 62nd percentile, higher the ~50 norm for high school and college males. That is, I was ranked more “feminine” than the typical high school or college male.

In the Notes column on the profile sheet, I wrote the following:

“It is interesting that I personally scored consistently higher than the college male norms and the high school male norms. This seems to imply that I have a stronger and/or more developed character than the norms of these two types. However, it is further interesting to note that this applies to the category of femininity, which seems to imply that I have more female characteristics than the ‘normal members’ of these two groups.

“(However, rest assured that this does not mean that I am a homosexual.)”

Rereading these words a few days ago, my heart sank.

Why did I feel the need to assure the world that I was not a homosexual – especially when I knew that only Doc Copeland and I would likely ever see this profile?

The answer is that while I was comfortable with other people being homosexual, having internalized a subtler form of homophobia, I did not want anyone to think I was homosexual.

Ouch.

The idea of being more “feminine” – whatever that even means – had clearly struck a nerve, and the unnecessary parenthetic comment reeks of “methinks I doth protest too much.” That was certainly Nell’s reaction when I read the commentary to her.

It is true that I did not conform to traditional masculine stereotypes. I had zero interest in athletics or other outdoor activities like camping or hunting. I was quiet, polite and bookish, having gone 17 years with only one, very brief, fistfight. I was an expert driver, but I knew nothing about cars or motorcycles. I was extremely neat in my attire and environment, perhaps even a bit prissy – if that is a word anyone still uses. I did not drink alcohol, smoke or take any drugs except caffeine (and sugar). I never behaved aggressively sexually, remaining a virgin until nine days before I turned 20.[4]

And so forth.

Then again, non-athletic virginal bookworms were more likely to be labeled “nerd” than “gay,” or the more vicious f-slur, in the 1980s. Nearly every boy at Harriton – an upper middle class white suburban high school – dressed as preppily as I did.

Was I reacting to something within me? Looking back, I had a few male friendships around that time that were exceedingly close – what today would be called bromances. One of these male friends and I bickered constantly, a bit like an old married couple.[5] A few months later, we had what could only be described as a rancorous breakup.

Nonetheless, I have never been drawn to men romantically or sexually.[6] Very close male friendships were far more common in the 1980s than they are now. One can possibly read those as queer four decades later, but I feel I am unqualified to do so.

Perhaps because my life is a series of dualities and differential identities, I have long been drawn to queer stories and characters. I was adopted in utero, spending all a but few days of my life with a non-genetic family I loved, but still differed from in obvious ways. Raised Jewish, I had two non-overlapping sets of friends: secular and congregational. After my parents separated when I was 10 years old, I changed schools – and thus needed to find new social groups – multiple times. My 8th grade friends and I formed a nation called The State of Confusion and seceded from the Bala Cynwyd Middle School cafeteria early in 1980. In Chapter 10 of INTERROGATING MEMORY, I characterize my inter-high-school friends as “a motley crew of bookworms, misfits and romantics, a suburban adolescent Algonquin Round Table.” As noted, at least three of them later came out as gay. In the summer of 1982, a female friend threw a surprise candlelit birthday lunch for a mutual male friend – laid out on a tablecloth on the floor of a quiet section of the Gallery at Market East, a shopping mall in Center City Philadelphia.

Are all these aspects of a queerness beyond sexual orientation and gender identity? While I feel unqualified to answer this question, I would strongly embrace this definition of queerness – and I observe that Nell’s and my younger child is queer in the sexuality/gender sense.

For all that my idiosyncracies, someday to be the subject of a book, might fit a much looser definition of queer, though, the simplest and saddest explanation for the parenthetic comment on my CPI profile sheet is a horror at the idea anybody would think I was gay early in 1984. It is not an excuse to say I suspect every one of my friends and classmates felt the same way.

We still had a long way to go, and I apologize for the lack of understanding I showed when I was 17. I will be a stronger ally going forward.

Until next time…and if you like what you read here, please consider making a donation. Thank you!

[1] Laibson, David, “’Doc’ Will Not Teach Psych. in ’84-5,” Free Forum (Rosemont, PA), June 8, 1984.

[2] In terms of specific occupations, I was Similar to Geographer, Sociologist, Psychologist, Librarian and Public Administrator. Here the assessment falters somewhat.

[3] My age is listed as 14, which I turned on September 30, 1980, while the season is Fall 1980.

[4] In the strict sense of vaginal intercourse, anyway. My girlfriend my freshman year at Yale did everything but that.

[5] He, his girlfriend and the girlfriend’s best friend – to whom I was mutually attracted – were the three friends I drove to Trenton that night in April 1984.

[6] I note without comment here that pornography can provide a safe place to explore certain curiosities.

One thought on “Queer confessions”