When I completed the final draft of the first edition of Interrogating Memory: Film Noir Spurs a Deep Dive Into My Family History…and My Own in January 2021, I had already learned a great deal about my paternal great-grandfather David Louis Berger; I had known next to nothing about him before I began to write in July 2017. His 1906 Petition for Naturalization (“PFN”) told me he was born in Pruzhany, in what is now Belarus, on October 15, 1869. His headstone at Har Nebo Cemetery in Philadelphia revealed his father’s name is “Shmuel Mayer;” I do not know his mother’s name. The 1910 United States Federal Census (“US Census”), conducted April 15, 1910, records “Louis” and his wife Ida (Rugowitz) had been married for 19 years, meaning they wed at some point between April 15, 1890 and April 14 1891. This fits with their first child, my grandfather Morris (Moshe), having been born in August 1893 – unless it was October 1892. I had even learned a fair amount about his life in the United States, culminating in his tragic death on October 23, 1919, just after he turned 50.

That death – which I describe in Chapter 1 – made the front page of The Philadelphia Inquirer, which published this photograph of Louis Berger:

I had one other piece of information: the name of the ship that carried my great-grandfather to – not Philadelphia, but Quebec City, in the Canadian province of Quebec:

“According to his Petition for Naturalization (“PFN”) – dated October 26, 1906 and witnessed by Ida’s first cousin Max Rugowitz and Harry Berman, brother-in-law of Ida’s brother Charles – Louis, Ida and their four children left ‘Russia’ on ‘May 5, 1898’ on the ‘SS Tungorahra,’ eventually arriving in Philadelphia by way of Quebec.

“’Tungorahra’ is almost certainly how either Clerk William W. Craig or Deputy Clerk Charles T. Humphrey, depending on who actually completed the PFN – Louis Berger’s signature is in a different handwriting – transcribed the name ‘Tongariro.’ This steamship was built in Glasgow, Scotland by J. Elder and Company, and first launched in August 1883, serving the London-to-New-Zealand route.[1] This 389-foot-long vessel held 80 1st class cabins ($50.00 each), 80 2nd class cabins ($34.00) and 250 steerage cabins ($22.50); in 2019 dollars, they cost $1,540, $1,047 and $693, respectively.[2] On August 6, 1898, three months after the Berger family supposedly boarded it, the Tongariro began to service the Liverpool-to-Montreal route, with stops in Londonderry, Ireland and Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It made seven additional voyages on this route, with the final one commencing on May 6, 1899, arriving in Quebec City on May 16 and Montreal on May 17.

“Without ship’s manifests, I cannot say for certain which of the Tongariro’s eight Quebec-ending voyages carried Louis Berger and his family to North America.”

This is where matters stood until around June 2022.

***********

One of the most famous scenes in the Marx Brothers’ 1935 masterpiece A Night at the Opera is when the characters played by Chico and Harpo Marx, along with Alan Jones – who just traveled by steamship to New York City as stowaways – explain how they “fly to America” on a steamship.

The story of how Louis Berger and – eventually – his wife and children came to America is not nearly as funny, though it is quite “indirect,” as the Mayor puts it to Harpo after Chico’s remarks. It begins when I returned to Ancesty.com sometime after May 24, 2022, the official publication date of Interrogating Memory. Before I tell that story, however, I engage in some speculation.

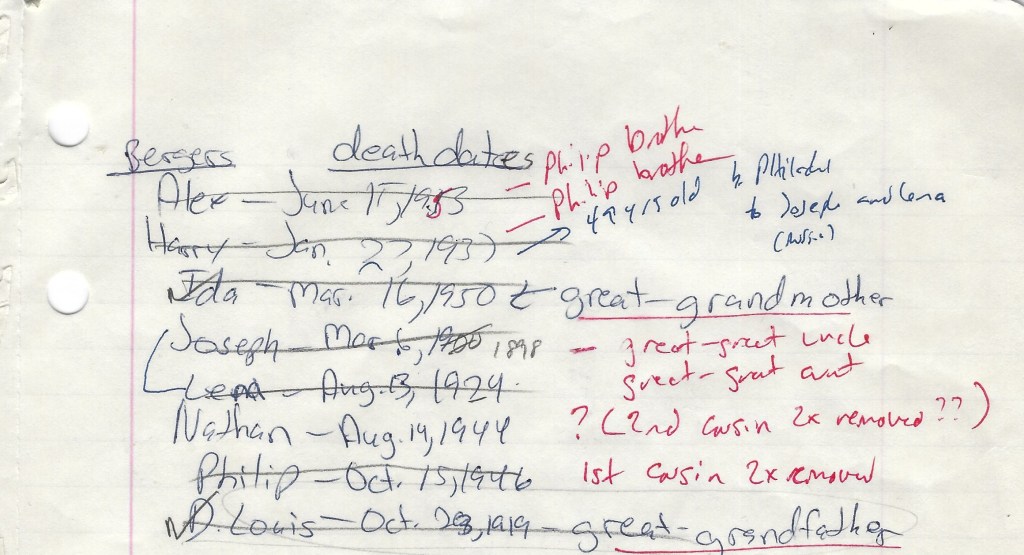

In the late 1970s, my father helped me to prepare this list of “Bergers death dates.” I do not recall why, though it is reasonable to assume these are somewhat close relatives. They are buried in three different Philadelphia cemeteries, so we were not taking names off headstones. It is not part of my elementary school genealogy project; the paper is different. Curiously, the most recent date is 1953, one year before my father’s father Morris died. The names are also in alphabetical order, other than my paternal great-grandfather.

When I began to write Interrogating Memory, I rediscovered this document in my filing cabinet, in a folder labeled “Berger.” I immediately recognized two names: my paternal great-grandparents D. Louis and Ida (Rugowitz) Berger. Both dates of death are accurate.

The other six names, however, were unfamiliar to me. Through Ancestry.com, I quickly identified “Joseph” and “Lena” as the parents of “Alex,” “Harry” and “Philip.” My initial conclusion – that Joseph was my paternal great-grandfather’s older brother – was proved incorrect when I found his headstone at Chevra Bikur Cholim Cemetery in Philadelphia, Joseph’s Hebrew name was “Shlomo Ahron bar Yitzchak,” meaning his father’s name was Yitzchak, or Isaac – and not Shmuel Mayer. He also died – aged only 37 – in 1898, not in 1900; month and year are correct.

My next conclusion, then, was that Isaac and Shmuel Mayer were brothers. This left only Nathan Berger, who proved a bit of a puzzle. Long story short, I eventually found a Nathan Berger buried in Roosevelt Memorial Park who died on August 14, 1944; my paternal grandfather and three of his siblings are buried there as well. Nathan Berger was the youngest child of Solomon and Edith Berger. According to Solomon Berger’s headstone at Roosevelt Memorial Park, HIS father’s name was…David.

I thus conclude, pending further evidence, that David, Isaac (Yitzchak) and Shmuel Mayer Berger were brothers. Other circumstantial bits of evidence exist. The sons of Joseph and Lena Berger lived near Congregation Beth El at 58th and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia, where Morris Berger served as Congregation Vice President.[3] When Solomon’s oldest son David died on May 7, 1938, he lived at 4800 Pine Street; Morris Berger lived with his wife Rae and their children Hilda and D. Louis just one block west, at 4919 Pine Street. And so forth.

***********

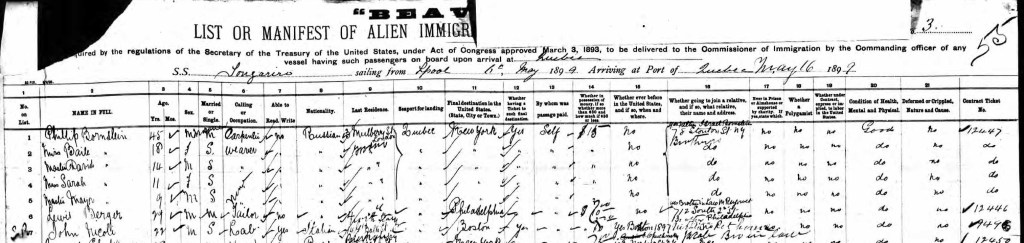

Returning to early June 2022, I finally found the passenger list for the voyage of the SS Tongariro which left Liverpool, England on May 6, 1899; Louis Berger was one year off in his recollection. It is conceivable he boarded the boat – on the loading berth on the west side of Hornby Dock[4] (which then sat just south of Gladstone Dock and just north of Alexandra Dock) – the evening before sailing, accounting for the incorrect day of the month.

From this page and blown-up image below, we learn “Lewis Berger” – ticket number 12446 – was a 29-year-old married male tailor. He was in steerage, along with 330 other adults, as well as 56 children and 18 infants. The “do” marks in pencil take us to the top of the page, where the following is written: “Constantin, London, 27/4;” I admit with chagrin I noticed those notations only a few days ago. We return to the Constantin shortly.

But the most striking thing about this page is what is NOT there: the names of his wife and children, at least three of whom were alive in May 1899; the fourth, Anna, was a bit of a puzzle until recently. I scoured the entire manifest and found no record of Ida, Morris, Rose and Mae. Meanwhile, more digging through Ancestry “Passenger List” files brought me to the manifest from the other end of the voyage:

With much more detail, we learn “Lewis” could neither read nor write.[5] He was of “Russian” ancestry – specifically the province (or gubernia) of Grodno; these fit with living in Pruzhany. The most recent address is difficult to read, though it is almost certainly a London address: 4 North Ham-something. We also return to this shortly.

“Lewis Berger” disembarked at Quebec City on May 16, 1899, having never before entered the United States/North America. He had already booked passage by train, using his own money, to his final destination: Philadelphia. Awaiting him there was “M. Rugowitz” of 712 S. 2nd Street. This is Charles Rugowitz, his wife’s older brother, who had established himself as a successful baker and philanthropist who relished his role orienting newly-arriving “greenhorns” to life in the United States.[6] When “Lewis Berger” left the Tongariro, he carried $20 with him, about $705 in 2022 dollars. He was not a polygamist, was under no contractual obligation in the United States, and had never been in prison or been a public charge. Finally, he was in good physical condition.

***********

We now return to the Constantin, which arrived in London on April 27, 1899, carrying 27 passengers who planned to board the Tongariro on May 6. I can find very little about this cargo ship built in 1870 by Scott Shipbuilding & Engineering Company; it was originally christened the Haco. In 1875, it switched to French ownership, who renamed it Constantin.

As of April 1899, when it was owned by Brown & Corblet, it was ferrying passengers from what I first thought was “Liban” in the London newspapers.[7] But since “Liban” meant the nation of Lebanon, this could not be correct; ship destinations were always cities. Looking closer, I realized the final letter was “u,” not “n.”

Bingo.

Libau is what Germans (and, thus, Yiddish-speaking Jews) called the Latvian port city of Liepāja. Like Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and Bremen and Hamburg in Germany, it was a place Jewish immigrations boarded a westward-bound ship for London/Liverpool. Liepāja is about 275-300 miles due north – and a bit west – of Pruzhany; presumably rail travel existed between a major city like Brest (about 30 miles southwest of Pruzhany) and Libau.

The implication from the London newspapers is that the Constantin sailed directly from Liepāja to London. Given this requires sailing north around Denmark to pass from the Baltic Sea to the North Sea, though, it is just possible its passengers alighted at Lubeck, Germany then traveled by rail 30 or so miles southwest to Hamburg, from where another ship ferried them to London; the Minerva arrived in London’s Tilbury Dock from Hamburg on April 27.[8] I find no record of when it left Hamburg.

I had long presumed emigrants from the Pale of Settlement (“Pale”), the vast Jewish area on the western fringes of the Russian Empire, traveled west across northern Europe to reach port cities like Hamburg. Perhaps some did. But traveling north within the Pale to a city with a substantial Jewish presence to board a westbound ship is logical. And if that ship arrived in London on April 27, leaving Libau around April 23 makes sense. This suggests Louis Berger began his journey to Philadelphia around April 20, though these dates are pure speculation.

Once in London, Louis Berger would have lived with a welcoming Jewish family in the East End until boarding a train for Liverpool. While many such transmigrants stayed at the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter, which opened on Leman Street on April 11, 1886 before moving to Mansell Street, neither address matches the Tongariro manifest. Close examination of an 1894 ordnance map of Whitechapel reveals a Northampton Street in the upper-right-most section, but I now suspect the recorder wrote “4 North Hany” Street, where “Hany” is an abbreviation for Hanbury Street.[9] There has never been a “North” Hanbury Street, but number 4 was located on the northernmost segment. And while this is admittedly a stretch, no other street name matches, and Liverpool-Street Station is only a few hundred yards to the west.

Incidentally, this is why “Hanbury Street” might ring a bell; I discuss other Jewish connections to the East End of London in 1888 here.

Louis Berger likely spent eight nights in London before boarding a train for Liverpool on May 5. The journey by train today takes about 3 hours, and it was probably not much different in 1899. Once Louis arrived, he boarded the ship, accouting for his recollecting “May 5.” The Tongariro actually deaprted on May 6 under Captain Robert Miller. By one account, the crossing “was a most enjoyable one, [as] the passengers held a series of concerts, with the result that the Montreal Sailors’ Institute will be augments by ₤5 12s.”[11] The ship was quite luxurious, as an article in the May 23, 1899 edition of the Montreal Gazette reveals, but how much of that luxury was enjoyed by the 405 steerage passengers crowded into 250 berths is unclear.

On the morning of Monday, May 15, the Tongariro passed “Cape Magdalen”[12] (Magdalen Islands), just north of Prince Edward Island; a few hours later it passed Anticosti Island before turning sharply southwest into the St. Lawrence River. At midnight, it passed “Father Point”[13] (Pointe-au-Père) on its port side, about 200 miles north of Quebec City. At 10:30 am on Tuesday, May 16, it passed “Grosse Isle”[14] (Grosse Ile), likely on its starboard side, meaning it was only about 40 miles from Quebec City. A few hours later, the Tongariro docked in Quebec City, and my 29-year-old paternal great-grandfather stepped on North American soil for the first time.

On the morning of May 17, a “special train with 230 Galicians arrived…at the Bonaventure Depot [in Montreal] from Quebec, en route for New York.”[15] It is plausible my great-grandfather was on this train. Galicia was an area of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that encompassed parts of southeastern Poland and southwestern Ukraine, bordering the Pale to the southwest, as the map above shows. A Szmul Maier Bergier was born in Izbica, Poland, just north of that border (a bit south of Lublin), in 1834; he could well be my paternal great-great-grandfather.

But why…Canada?

When mass Jewish immigration to the United States began around 1880, it was a (relatively) simple matter to take a steamship to Quebec City or Montreal then ride a train the short distance south into Vermont or New Hampshire, thus “avoid[ing] the trouble and delay of U.S. immigrant inspection,” especially after passage of the Immigration Act of 1882. However, that changed in 1894.

…[t]his evasion of immigrant inspection spurred the U.S. government to action. In 1894 the U.S. Immigration Service entered into an agreement with Canadian railroads and steamship lines serving Canadian ports of entry to bring those companies into compliance with U.S. immigration law. The steamship lines agreed to treat all passengers destined to the United States as if they would be landing at a U.S. port of entry. This meant completing a U.S. ship passenger manifest form and selling tickets only to those who appeared admissible under U.S. law. Canadian railroads agreed to carry only those immigrants who were legally admitted to the United States to U.S. destinations.

For its part, the U.S. Immigration Service stationed immigrant inspectors at Canadian seaports of entry to collect the manifests and inspect U.S.-bound immigrants. The largest Canadian Atlantic ports were Quebec and Montreal (summer) and St. John and Halifax (winter). Furthermore, between 1895 and 1906 the U.S. placed inspectors at northern land border ports of entry. Beginning in 1895, immigrants destined to the United States were subject to the following procedure upon arrival in Canada: U.S. immigrant inspectors at seaports inspected immigrants bound for the United States after they passed Canadian quarantine. If admitted, the inspector issued each passenger a “Certificate of Admission” showing he or she had been inspected and admitted. Railroads required all passengers who landed in Canada within the last thirty days to present their Certificates of Admission before boarding a U.S.-bound train. Then, when the train stopped at the border [at St. Albans, Vermont], another U.S. inspector boarded the train and collected the Certificates of Admission. In this way, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) tracked and connected an immigrant’s arrival at the seaport and his subsequent physical entrance into the United States.

I do not really know why Louis Berger chose this “indirect” route to Philadelphia, though here is one possible explanation. Solomon Berger, who I speculate is Louis Berger’s first cousin, appears with his wife Edith and their five children in the 1900 US Census as residents of Philadelphia. One year later, however, they lived in Montreal, according to the 1901 Census of Canada; they returned to Philadelphia in time to be recorded in the 1910 US Census. Solomon likely had a sister named Sophia. She moved to Montreal with her husband Benjamin Saltzman sometime after 1901, living there until her death in 1951; perhaps she moved closer to her brother. And “Bergier” is a French surname. It is thus remotely possible relatives of my great-grandfather emigrated from the Pale/Galicia to Quebec, and Louis Berger spent some time with them before moving on to Philadelphia. This could explain why I have been unable to locate a single sibling of Louis Berger, though it is possible they simply never left Europe.

Either way, one day after May 16, 1899, Louis Berger boarded a train to New York City, where he switched to a train to Philadelphia, arriving – at some point before January 1900 – at Reading Terminal, along 12th Street between Market and Arch Streets. This ended a journey of nearly 4,500 miles – if he took the most direct route, which he clearly did not.

Regardless of when Louis Berger boarded that train in Montreal, when Charles Rugowitz met him at the Broad Street Terminal, then located on the northwest corner of Broad and Market Streets, in his horse-drawn bakery wagon. He then his brother-in-law about 1w blocks east and nine blocks south to the corner of South 2nd and Kenilworth Streets, barely a few hundred yards west of the Delaware River. There, after a hot bath, he would have been fitted with new garments before settling down with Charles, his wife Rebecca (whom everyone called Perl) and their five young children – Louis’ two nieces and three nephews – for a supper of “cabbage soup, potted brisket, potato kugel and a pudding of cooked carrots and prunes.”[16] These familiar dishes were followed by a new, American dish: apple pie. Finally, over glasses of hot tea and lemon, Charles and Louis would have discussed the latter’s future. He is listed on the Tongariro manifest as a tailor, but he soon became a butcher, grocer and delicatessen owner.

And here is where the story resumes in Chapter 1.

***********

Well, two questions remained to be answered. First, why could I find no record of Louis Berger in the 1900 US Census if he arrived in May 1899? Second, when did his wife Ida and (at least) three of their children arrive in Philadelphia?

It turns out I needed to answer the second question before I could answer the first question. Having found Louis Berger in the record of ships leaving from Liverpool, albeit with the benefit of knowing the name of the ship and approximate date of departure, I set out to find Ida and the children in similar records. But rather than do a simple search, I wasted hours in the summer of 2022 literally leafing through thousands of pages of manifests of ships departing from Liverpool, beginning in January 1898. In retrospect, this was…foolish.

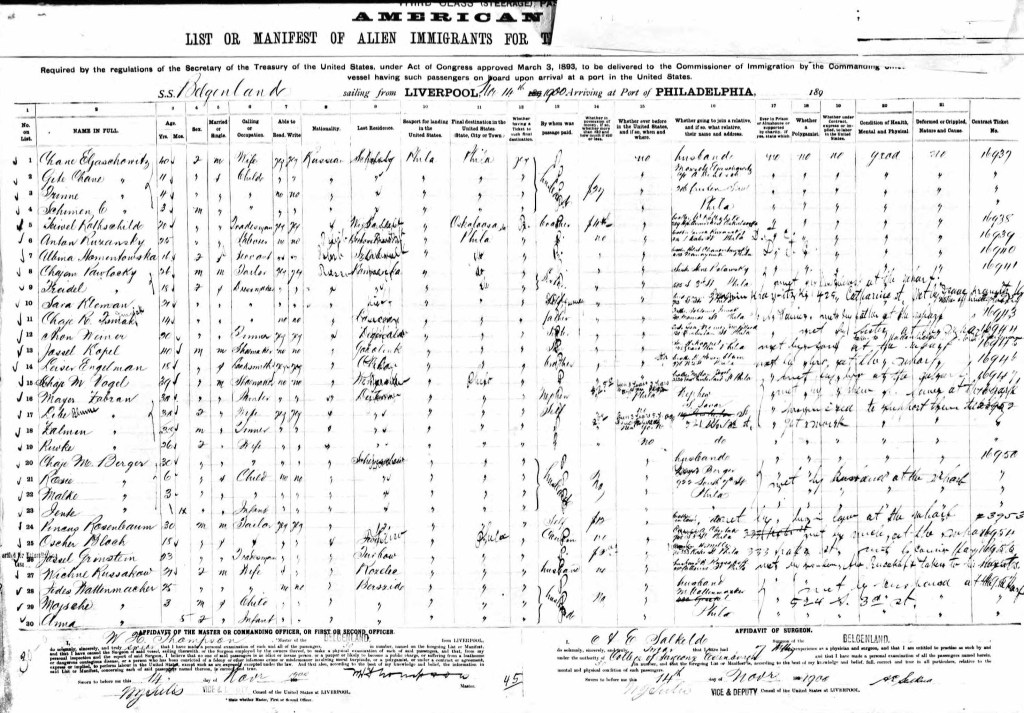

After taking a break from family research for a few months, I returned to Ancestry.com in early December 2022. And once I recalled Ida’s Hebrew name was Chaje Miriam, I quickly found this page from the manifest of the SS Belgenland, which left Liverpool, bound for Philadelphia by way of Queenstown, Ireland,[17] on November 14, 1900.

This blown-up fragment shows that among the passengers are “Chaje M. Berger” and her daughters Rosie, Malke (Mae) and Yente (Anna).

Ida, a 30-year-old married woman, can read and write, though her daughters, aged six, three and 11 months, cannot. It is hard to read, but these Russians bound for Philadelphia have left “Shershova,” which is the town of Sarasova, 10 miles east of Pruzhany. Louis Berger’s obituary[18] reveals he was a member of the “Prueshiner Sheswer Lodge No. 132,” referring to the Prushin Shershow Beneficial Association, a landsmanshaft, or society formed by Jewish immigrants from the same town. It was founded in Philadelphia in September 1889, possibly by Charles Rugowitz himself. A reasonable surmise is that Ida and her then-three children moved to Sarasova to live with relatives after Louis left in April 1899.

“Chaje M. Berger” and her daughters carried no money – Ida’s husband paid for the ticket – and had never been in the United States. None of the four were polygamists, under contractual obligation to anyone in the United States, nor had ever been in prison or been a public charge. And they were met at the dock of the Washington Street pier on November 28, 1900 by Ida’s husband, Louis Berger of 922 S. 7th Street.

According to the 1900 US Census, the family of Jacob Trumper lived at that address on June 8, 1900. Jacob Trumper is married to the former Hannah Rugowitz, Ida’s older sister. Along with their sons Abraham, Max, Charles and Julius they lived with a boarder. The name looks like Louis Boyer, but it is Louis Berger, a 30-year-old Russian-born tailor who could neither read, write nor speak English. Basically, one brother-in-law arranged for Louis Berger to live with another brother-in-law. The garbled surname explains why I could not find this record until now.

And now the mystery of where and when my great-aunt Anna Berger was born is (mostly) solved. The date Louis left Pruzany/Sarasova – on or about April 20, 1899 – is the latest date “Yente” could have been conceived. Nine months later puts one in late January 1900. Meanwhile, 11 months prior to November 28, 1900 is December 28, 1899. Splitting the difference, we say that Anna Berger was born in late January 1900 in Sarasova, in what is now Belarus; it remains unclear, however, why her date of birth is February 15, 1898 on her father’s PFN. Anna Berger Halbert died on December 19, 1999 – meaning she lived during all but a month or two of the 20th Century.

Moreover, when Louis Berger met his family on the Washington Street pier on November 28, 1900, it was the first time he saw his fourth child. The family soon moved to a house at 105 Kenilworth Street, just west of Front Street (and the Delaware River), and just one block east from Charles and Perl Rugowitz.[19] Presumably, their eldest child – my paternal grandfather Morris Berger – moved with them, but here things get…confusing.

***********

Two things are clear. One, Louis Berger traveled by himself from Pruzhany to Philadelphia in April/May 1899 in order to establish a presence there. This allowed his wife and children to avoid detention under Section 2 of the Immigration Act of 1882, which allowed any noncitizen to be denied (at least, temporarily) entry who is a “convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” In fact, my maternal great-great-grandmother Chave Koslenko and two of her granddaughters were detained as “LPC” (liable to become a public charge) on Ellis Island from April 7 to 1:20 pm on April 10, 1912 after taking the SS Campanello from Rotterdam, The Netherlands. They were fed breakfast, dinner and supper, though, until her son Samuel Goldstein of Philadelphia presumably made contact with someone named “Fitzgerald.”

Two, Morris Berger did not accompany his mother and sisters in November 1900.

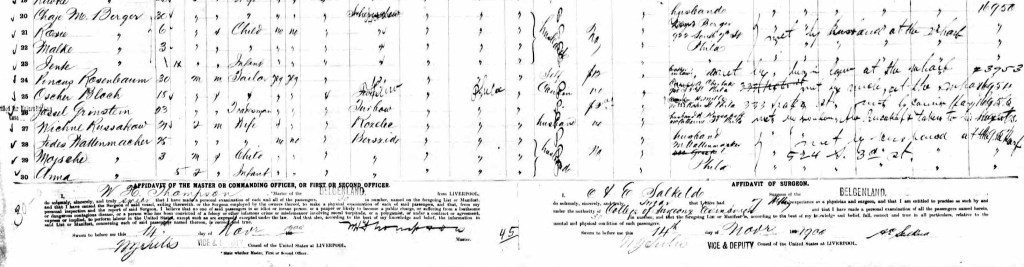

It is likely, then, he arrived in Philadelphia between May 1899 and November 1900. The only possible match is from the January 4, 1900 American immigration list of passengers on, curiously, the SS Belgenland.

Here is the key section:

We find a “Mokes Birger” traveling to Philadelphia to meet what COULD be “Mr. Louis Berger” at 525 S. 4th Street; the number 626 is crossed out (there was no such address in the 1900 US Census). [Update August 13, 2023: in 1900, Washington Hall – a local meeting place for Jewish workers and other groups – was located at 525 S. 4th Street, while a 1910 street map clearly shows a home at 626 S. 4th Street. The search continues.] Father – who paid for his son’s ticket – met son “on the wharf,” meaning the Washington Street pier. “Mokes Birger” is a 10-year-old single male of Russian ancestry who can read and write; Morris Berger was actually six or seven at the time. He is in good physical condition. The actual manifest recorded in Liverpool makes clear his first name is “Moses,” which is what his/my Hebrew name Moshe means. It also reveals he is one of 10 passengers to have landed in London on the Schwalbe. This ship had arrived from Bremen in St. Katherine’s Dock in London on January 1. If this truly is my paternal grandfather, he was literally en route to his new country when the 19th Century became the 20th Century. He also had a rough passage: the Belgenland, carrying 41 cabin and 83 steerage passengers, “left…one day late and was further retarded by heavy weather.”[20] They passed what appeared to be a sunken wreck on January 10.

Accompanying “Moses” was a 17-year-old single female dressmaker of Russian descent named Chane Silberbarg, on route to visit her sister Leah; the latter was living not at 504 S. 5th Street, but at 229 S. ??? Street; it COULD be 229 South Street. I note 504 S. 5th Street is only one block west of 525 S. 4th Street. It matters little, however, as by June 6 (per 1900 US Census), the two sisters were boarders at 314 N. 2nd Street, home of Louis and Annie Kovitsky and their five daughters.[21] They are listed as Lena and Annie Silver, and they are “shirtmakers,” possibly meaning they toiled in a sweatshop; neither could read, write nor speak English.

Finally, the two were traveling from “Mankovicz,” which I know from other records is Minkovitz (or Myn’kivtski) in what is now Ukraine. Chane returned to the Pale at some point, where she married Abraham Bortmann and had a daughter named Chaved (Eva). The three of them, along with her parents (Abraham and Freida) and three sisters returned to Philadelphia on the SS Noordland on September 2, 1906. The manifest clearly says “Minkowitz” for Bortmann and “Podoli” for the Silberbargs; “Podoli” refers to the Podolia province of the Pale, in what is now southwestern Ukraine. They were going to Chane’s brother Isaac Silver, who had been living at 527 Vine Street.

And here is where things get interesting.

Also living at that address in 1906 were Nathan Berger and his sons Julius, Louis and Max. Nathan arrived in Baltimore, MD on September 14, 1896 from “Kohdrubka” in “Austria.” His in-laws, who were also on the SS Italia, came from “Kamienec” in “Austria.” For Jews in 1896, “Austria” meant “Galicia,” and these towns are Kolodribka and Kam’yanetz’-Podil’s’kyi (“K-P”) in Podolia – right on the border between Galicia and the Pale. Minkovitz is about 25 miles northeast of K-P. Meanwhile, on his death certificate, Nathan Berger listed his parents as Isaac Berger and Devorah Klemky. I surmise this is the same Isaac Berger who is the father of Joseph Berger.

There is no way he travels to the United States as a child without a close family member to accompany him. IF “Moses Birger” is my paternal grandfather, Chane Silberbarg must be a cousin of some kind. If her mother Frieda is Louis’ older sister, born in October 1858[22], Chane Silberbarg and Morris Berger are first cousins, and Isaac Silver is the second cousin of the three younger Berger men with whom he shared 527 Vine Street.

Alternatively, Frieda’s father is Isaac Berger – making Chane Silberbarg and Morris Berger second cousins, and the younger Berger men her first cousins. This is where I have currently landed. Unfortunately, however, Freda Silver’s death certificate lists neither parent’s name, and I have not yet seen her headstone in Upper Darby’s Har Jehudah Cemetery.

A final possibility, of course, is that “Moses Birger” is NOT my paternal grandfather, and this is all a wild goose chase. And here I pose key questions. Why travel from Minkovitz, which is about 300 miles southeast of Pruzhany? Why did he not accompany his mother and sisters in November 1900? Why can I find no record of him in the 1900 US Census? Why was Louis Berger living at 525 S. 4th Street in January 1900 (IF he was)?

Here is one plausible scenario.

Louis Berger leaves for Philadelphia in late April 1899. His wife Ida and their three children move to Sarasova to live with relatives while Louis establishes himself. He does so within a few months and sends for his family. However, Ida has since discovered she is pregnant. Choosing not to travel until her fourth child is born, but knowing her precocious older child is missing his father, she decides to send him to Philadelphia accompanied by a trusted relative. She learns the daughter of her husband’s first cousin is traveling to visit her sister in Philadelphia that December. The cousin lives 300 miles south, however, so she must travel with him to Minkovitz. From there, Morris and his cousin Chane leave for Philadelphia, making their way to Bremen, then London, then Liverpool, then Philadelphia, where father and son reunite on the Washington Street pier. Louis Berger has been living wherever there is space – I have yet to find a link between the residents of 525 S. 4th Street as of June 1900 and Louis Berger, then decides his son will live with the latter’s first cousin by marriage Lena until Morris’ mother and sisters arrive. To be closer to his son, he moves in with his in-laws a few blocks south, where he is curiously listed as “single.” When Census enumerator Charles Bowen arrives at 702 Clymer Street on June 13, Morris is conveniently out of the house, and thus never gets counted; this avoids unwanted questions. Five-and-a-half months later, the Berger family is reunited on the Washington Street pier, and they move into a rented house at 105 Kenilworth Street.

Still, all of this is merely speculation until I learn whether Freda Silver[23] is a “Berger,” making this how (at least) five of the six Bergers flew by steamship to America, where A Night at the Opera was released just one month and five days before my father was born.

Until next time….and if you like what you read on this website, please consider making a donation. Thank you.

[1] http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/descrptions/ShipsT-U.shtml Accessed December 19, 2018

[2] Advertisement for “Beaver Line Royal Mail Steamships,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), August 9, 1898, pg. 11

[3] “Beth-El to Hold 44th Meeting,” Philadelphia Jewish Exponent (Philadelphia, PA), May 23, 1952, pg 14

[4] Advertisement for “Beaver Line Associated Steamers, Limited.,” The Liverpool Mercury (Liverpool, Merseyside, England), May 1, 1899, pg. 12

[5] He was able to do both by April 1910, according to that year’s US Census, after taking what I suspect were night classes.

[6] Lipscott, Alan, 1953. “The Story of Mr. Rugowitz: The Life and Progress of an Immigrant.” Brooklyn Jewish Center Review, May 1953, pp. 10-11, 22.

[7] e.g. “LONDON SAILINGS.” The Standard (London, Greater London, England), April 13, 1899, pg. 8

[8] “LONDON ARRIVALS, AND THE DOCKS THE VESSELS GO INTO.” The Standard (London, Greater London, England), April 28, 1899, pg. 10

[9] I can almost hear my Yiddish-accented paternal great-grandfather pronouncing “Hanbury” as “Hanry.” The American immigration officer stationed in Quebec City (as of 1894) simply transliterated what he heard, being disinclined to search London street maps. That is my job.

[11] “The S.S. Tongariro.” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), May 18, 1899, pg. 8

[12] Column headed “SHIPPING,” The Liverpool Mercury (Liverpool, Merseyside, England), May 16, 1899, pg. 10

[13] “The gulf.” The Montreal Star (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), May 16, 1899, pg. 7

[14] Ibid.

[15] “CITY AND DISTRICT.” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), May 18, 1899, pg. 3

[16] Lipscott, pg. 10

[17] “Arrived Yesterday” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), November 29, 1900, pg. 12

[18] “BERGER,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), October 26, 1919, pg. 23

[19] A grocer named Louis Berger lived there from 1902 to 1905, according to the Philadelphia City Directory for those years. In 1906, the family moved to 2241 Callowhill Street.

[20] “Arrival of the Belgenland,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), January 19, 1900, pg. 11

[21] Fully 23 people lived at this address on June 6, 1900, which is now in the shadow of the Vine Street Expressway. I have yet to find familial connection between the Silver sisters and the Kovitsky family.

[22] Or 1868 – the record is contradictory.

[23] Who died from skull fractures and other internal damage after being struck by a trolley car at the corner of 31st Street and Montgomery Avenue, in Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, shortly before 10 pm on September 17, 1920. She lived only three blocks north, at 3137 Euclid Avenue. Taken to Northwest Hospital, she died three days later. “WOMAN HIT BY CAR; Found in Street By Motorist With Fractured Skull,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), September 18, 1920, pg. 3

Love it! It never would have occurred to me that they went to Canada THEN to Philly! Hamburg has been a frustrating dead end for me as well in my own family research. I even had a friend I know who lives in Hamburg check out the city archives in case there were any documents that might not have been put online.

Apparently he told me after checking at some point the city archives ran out of physical room for files and decided to burn all records before a certain date-hence a dead end. I can’t tell you how disappointed and devastated I was-the records I needed had been completely destroyed in this process.

Also Marx Brothers are always a loved classic in my house! Duck Soup is one of my personal favorites. Happy New Year to you and your family Matt!

LikeLike

Happy New Year to you as well! One of these days, we will head down to you for a proper visit. Thank you for reading this essay – I was going to send you and your mother a link. The search for new information – and the revised, updated paperback edition of Interrogating Memory – never ends. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sent this link already to my mom! We both found it very interesting! Love the fact that the ship they came on was called MINERVA absolutely blew me away! 😱

LikeLike