One Saturday night when I was about nine years old, I found myself lying in bed, leafing through a hardcover book of biographical sketches while half watching a movie on the small black-and-white television set in my bedroom. Perhaps I was watching a film starring Spencer Tracy, because at one point I turned to his entry in the book.

When I found it, I let out a kind of animalistic cry of anguish. It was loud enough that my mother, two closed doors and a short, carpeted hallway away in her own bedroom, came to see what was wrong.

Through my tears, I cried out, “Spencer Tracy died!”

Flash forward to this past Thursday afternoon. At about 3:30 pm, I noticed I had a text message from my wife Nell. My brain misread part of it as, “I am so worried about David Lynch.”

I knew the iconoclastic director and painter had revealed a diagnosis of emphysema the previous July, so I quickly checked online. It took me a few seconds to process “January 16, 2025” under “Died.” Just as I had misread “I am so sorry about David Lynch.”

When it finally clicked, though, I let out a similar animalistic cry of anguish.

One of my greatest heroes – who would have turned 79 the day I published this – was dead.

As recently as 10 years ago, David Lynch was only on the periphery of my cinematic consciousness, despite having seen four of his 10 feature films.

There is a section called Cinematic Freedom in Chapter 10 of my first book, Interrogating Memory. In it, I discuss a set of films I watched on HBO in the early 1980s that influenced my later film noir fandom. Here is how I describe one of them:

“Before watching these neo-noir films, I was captivated by two dark-hued cinematic explorations on HBO, one of the city and one of humanity. […] I likely watched the second film at 11 pm on January 23, 1982. While it is an emotionally-wrenching tale of alienation, photographed in gorgeous black-and-white by Freddie Francis, contrasting humanity’s light and dark sides, The Elephant Man is not film noir. Produced by Mel Brooks’ Brooksfilms, [David] Lynch’s second film was his first release by a major studio, Paramount Pictures. The Elephant Man is one of a handful of films I enjoyed once, but may have a hard time watching again.”

The next film directed by David Lynch I watched was Blue Velvet, though I do not remember when or where. It was released in the fall of 1986, when I started my junior year at Yale, so I might have seen it at the movie theatre on Broadway.1 Or one of Yale’s six film societies screened it my senior year. Either way, I did not love it – I was put off by the macabre tableau late in the film of the man with his ear sliced off and the corpse standing next to a lamp.

Which makes it even stranger that I watched Wild at Heart within a year or two of its release in the summer of 1990. Seduced by its romantic thriller advertising and Cannes Film Festival awards success, I still braced myself for the same sort of Grand Guignol imagery as in Blue Velvet. Sure enough, here comes Sherilyn Fenn with a gaping head wound wandering around the scene of a fatal car accident.

I did not recognize her as Audrey Horne from Twin Peaks at the time, though, because I did not watch the television series when it first aired. It was impossible not to be aware of it, of course, and I mimicked the backwards-talking “man from another place,” thinking the entire show was like that.

Despite the releases of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), Lost Highway (1997) and The Straight Story (1999), I then stayed away from Lynch until early in 2002, when curiosity got the best of me, and I rented a copy of Mulholland Drive, first released in the United States the previous October.

I was absolutely fascinated by it (despite being terrified by the early scene behind the Winkie’s restaurant) – and thoroughly confused. So much so, I spent much of the next day e-mailing folks to figure out just what the hell I had watched. I also read online interpretations, making Mulholland Drive the first of dozens of films for which I would seek internet clarification after viewing. A few years later, I recorded about two-thirds of it from TCM onto a DVD. While I replayed certain onanistic scenes, I did not rewatch the film it its entirely for more than a decade.

At some point in 2015 or 2016, I came across a clip on YouTube of David Lynch being interviewed by Jay Leno in 1992. The first thing Leno asks Lynch is what he thinks his characterization as a psychopathic Normal Rockwell means.

“Somewhat normal on the outside, and, umm, someone, uhh, that maybe is somewhat disturbed on the inside.”

Leno then asks, “Now what kind of kid were you? Were you a good student? Were you a pretty straight kid?”

“Umm, I was straight as an arrow.”

After some banter, Leno presses the point.

“So, at some point, you hit your head or something. Something happened. At what point do we sort of, does one tend to veer into show business? I mean, straight as an arrow…”

“I went to Philadelphia.”

Leno then throws back his hands and, while the audience laughs, says, “Ahh, say no more.”

Lynch goes on to explain – with convolutions reminiscent of my own story-telling – that he had not planned to attend art school in Philadelphia until, as he put it, “I found myself crossing this particular bridge in a bus. And, and, the next moment I was there.”

And here we veer into biography.2

In November 1965, Lynch took a bus north from Alexandria, VA to begin classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (“Academy”), still located in the Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building at 128 N. Broad Street, two blocks north of City Hall. He moved in with his friend Jack Fisk, also a student at the Academy. Fisk lived next door to the Famous Diner, then located at 116 N. 21st Street.3 Now Pete’s Famous Pizza, it was a seven block walk west on Cherry Street to the Academy.

Needing more room, on New Year’s Eve the two art students used shopping carts to move to a house they rented for $45 a month (about $451 today) at 13th and Wood Streets. Fisk described the house as…

“…across the street from the morgue in a scary industrial part of Philadelphia. People were afraid to visit us, and when David walked around he carried a stick with nails sticking out of it in case he got attacked. One day a policeman stopped him, and when he saw the stick he said, ‘That’s good, you should keep that.’”4

According to a 1962 map of Philadelphia, the city morgue stood at the northwest corner of 13th and Wood Streets, three blocks north and one block east from the Academy. The building now houses the McSherry Annex of Roman Catholic High School. The house was supposedly catercorner from the morgue, seemingly placing it at 321 N. 13th Street – or one of the four adjacent rowhouses to the south. That entire block of N. 13th is now a U-Haul parking lot. However, Lynch also says the house was “next door to Pop’s Diner,”5 meaning Pop’s Luncheonette at 325 N. 12th Street – one block east. Pop’s is now Wood Street Pizza.

Lynch described the house this way:

“Our place was like a storefront, and in the back was a toilet and a washbasin. There was no shower or hot water, but Jack rigged up this stainless-steel coffee maker that would heat up water and he had the whole first floor, I had a studio on the second floor next to this guy Richard Childers, who had a back room on the second floor, and I had a bedroom in the attic. The window in my bedroom was blown out so I had a piece of plywood sitting in there, and I had a cooking pot I’d pee in then empty out into the backyard. There were a lot of cracks in my bedroom walls, so I went to a phone booth and ripped out all the white pages…I mixed up wheat paste and papered the entire room with the white pages, and it looked really beautiful. I had an electric heater in there, and one morning James Havard came to wake me up and give me a ride to school and the plywood had blown out of the window, so there was a mound of fresh snow on the floor of my room. My pillow was almost on fire because I had the heater close to my bed, so he maybe saved my life.”6

This neighborhood, which Lynch described as “pretty weird,” was later christened the “Eraserhood” because its industrial aspect inspired the look of Eraserhead, his first feature-length film.7

Incidentally, Lynch lived when I was born on the 2nd floor of a former concrete-and-steel eight-floor textile factory at the southwest corner 3rd and Spruce Streets on the morning of September 30, 1966. As with many of Lynch’s Philadelphia homes and haunts, Metropolitan Hospital is long gone, euthanized by Edmund Bacon – Kevin’s father – during his early-1970s urban renewal program.

In April 1967, Fisk and Lynch moved to 2429 Aspen Street, less than a 10-minute walk west of Eastern State Penitentiary. Soon after, Peggy Reavey, another Academy student, moved in with Lynch as his girlfriend (though he called it “friendship with sex” for a time8). That August, Reavey told Lynch she was pregnant. Lynch did not return to the Academy for the fall semester, concluding his resignation letter, “Love—David. P.S.: I am seriously making films instead.”9

Lynch and Reavey married on January 7, 1968. With funds obtained from their parents, they bought a three-story house at 2416 Poplar Street, on the southeast corner of the intersection with Ringgold Street, for $3,500 (nearly $31,750 today). It still sits directly across Poplar from the stone walls surrounding Girard College.

According to Lynch, the house had…

“…twelve rooms, three stories, two sets of bay windows, fireplaces, earthen basement, oil heat, backyard and tree. […] It was right on the borderline between this Ukrainian neighborhood and a black neighborhood, and there was big, big violence in the air, but it was the perfect place to make [his short film] The Grandmother and I was so lucky to get it. Peggy and I loved that house. Before we bought the place it had been a communist meeting house, and I found all kinds of communist newspapers under the linoleum flooring.”10

Reavey recalled looking out of one of the bay windows and seeing the Ukrainian Catholic Church – also still there – directly across Ringgold.

To film The Grandmother, Lynch and Reavey turned the third floor of the Poplar Street house into a film set, knocking down several walls and painting the resulting space black, except for chalk where ceiling met wall. It was while making The Grandmother that Lynch met Alan Splet, “a kind of freelance genius of sound.”11 The sound effects they devised – and the film itself – remain deeply unsettling, yet beautiful in a uniquely Lynchian way.

Meanwhile, Jennifer Chambers Lynch was born on April 7, 1968. While “David got a kick out of Jen [he] had a hard time with the crying at night. He had no tolerance for that.”12 Nonetheless, Peggy Lynch recalled the three of them making a very happily family. Soon after Jennifer was born, two Academy graduates – Rodger LaPelle and Christine McGinnis – offered Lynch a job “making prints in a shop where they produced a successful line of fine-art etchings.”13

On November 20, 1969, Lynch wrote in a letter to his parents, “We feel that a miracle has occurred for us. I will probably spend the next month trying to get used to the idea of being so lucky, and then after Christmas Peggy and I will ‘roll ‘em’ as they say in the trade.”14 Lynch had applied for a $7,500 grant from the American Film Institute’s Center for Advanced Film Studies (“Center”) in Los Angeles, CA, submitting his short film The Alphabet plus the script for The Grandmother. But when Center Director Tony Vellani saw an early version during a trip to Philadelphia, he invited Lynch to be a fellow at the Center in the Fall 1970 semester.

After selling the Poplar Street house for $8,000 (earning the young couple the equivalent of about $44,750 in profit) in August 1970, Lynch drove west to Los Angeles with his brother John, Fisk and Fisk’s dog Five. Peggy and Jennifer arrived a few weeks later, and that was the end of David Lynch’s time in Philadelphia.

Nonetheless…

“Philadelphia had worked its strange magic and exposed Lynch to things he hadn’t previously been familiar with. Random violence, racial prejudice, the bizarre behavior that often goes hand in hand with deprivation – he’d seen these things in the streets of the city and they’d altered his fundamental worldview. The chaos of Philadelphia was in direct opposition to the abundance and optimism of the world he’d grown up in, and reconciling these two extremes was to become one of the enduring themes of his art.”15

He may have directed Eraserhead over five years in Los Angeles, beginning on May 29, 1972, but he was wholly inspired by living in Philadelphia in the second half of the 1960s. The first scene shot was the dinner scene at Mary’s house. The street number of the house is 2416 – same as the house on Poplar Street. Jack Fisk plays the Man in the Planet, pulling all the levers. Henry Spenser works as a printer as LaPelle’s – an homage to Rodger LaPelle. The industrial look of the film reflects Lynch’s time at 13th and Wood. And the entire film is centered around the entrapment Henry and Mary feel with their mewling “baby” – which may represent Philadelphia itself?

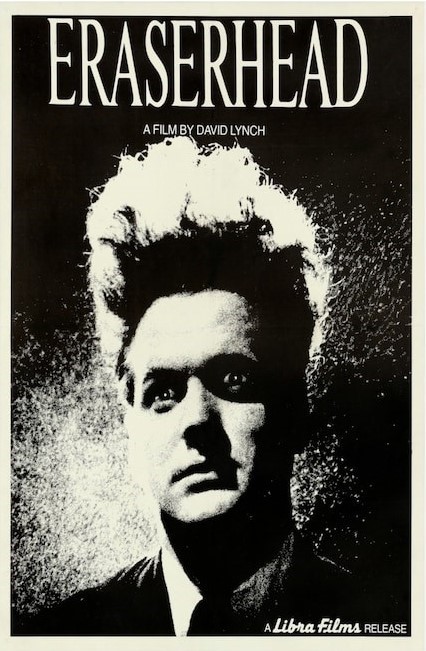

While I did not see Eraserhead for the first time until around 2018, I was certainly aware of it, mostly from its iconic poster, which seemed to be everywhere in the 1980s.

Although, as I began to venture into the city of Philadelphia with my suburban teenaged friends, I mixed up the film, which had multiple midnight screenings between November 1981 and May 1982 at the Theatre of the Living Arts at 334 South Street, with Zipperhead, the punk rock clothing store that until 2005 sat less than one block west, at 407 South Street.

Returning to the 1992 interview, meanwhile, I took it in stride that Leno was having fun with the notion of “becoming DAVID LYNCH by going to Philadelphia.” I liked to joke to people I met at Yale that I came from a small suburb between New York City and Washington, DC. Oh, really, where? Philadelphia.

Folks from New York City loved this quip. Everybody else just stared blankly at me.

No, what made me sit up and take notice was the gentle-looking man with kind eyes and a wry smile talking quietly and humbly about the artistic process. This was not at all how I had pictured, you know, DAVID LYNCH.

That interview led to other interviews – and a thorough reevaluation of Lynch’s work.

The exact order of viewing eludes me, but I think I began by watching the original Twin Peaks series. This was likely in 2016, because I was ecstatic when Showtime aired Twin Peaks: The Return over 18 nail-biting weeks in 2017. Then I watched all 18 episodes again – including the extraordinary Episode 8 twice. I watched dozens of videos on YouTube unraveling the events and meaning of each episode, while sharing the first season of the original series with our young daughters. We stopped there, deeming the idea of a father raping and killing his own daughter too scary and intense for them. Finally, I bought the soundtrack to the original series, marveling at the late composer Angelo Badalamenti’s ability to work with Lynch to create the perfect sonic moods. A shout out here also to the late Julee Cruise.

The point is, like so many other fans of David Lynch, what permanently drew me in was the mythical northwestern town he and Mark Frost created for ABC in 1990.

I then turned to the feature films, beginning (probably) with a rewatch of Mulholland Drive, followed by a first viewing of Lost Highway. The latter film inspired the opening to the Preface of Interrogating Memory:

“Early in David Lynch’s neo-noir film Lost Highway, Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) talks to two police detectives about mysterious videotapes he and his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) received in the mail. One detective asks if they own a video camera.

“No. Fred hates them,” replies Renee, to which Fred adds, “I like to remember things my own way.” Pressed, Fred elaborates: “How I remembered them. Not necessarily the way they happened.”

The remainder of the film reveals the surreal lengths Fred will go to remember things his own way, a theme Lynch later explored even more brilliantly in Mulholland Drive.

By contrast, I strive in this book to be the video camera Fred desperately wants to avoid. Spurred initially by the deceptively-simple question, “Why do you love film noir?” I began to write a straightforward account of the roots of my fandom. As I did so, though, I realized I needed to contextualize those roots through my suburban Philadelphia Jewish upbringing, the lives of my parents, and the lives of their parents, two of whom had left what was then called the Pale of Settlement as young boys to live in Philadelphia.”

After Lost Highway, I think the order of first-viewing was Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Eraserhead (1977) Inland Empire (2006) and The Straight Story. Now a full-fledged David Lynch fan, I still put off watching Dune until about four years ago. While I have little interest in watching it again, it was better than I had been led to believe.

And by full-fledged fan, I mean I dressed as David Lynch for Halloween in 2017. I even asked Tony at Beau Brummel Hair Salon to style my hair like Lynch, which – despite a valiant effort – did not quite work. I read Frost’s The Secret History of Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier while flying back and forth to San Francisco, CA for NOIR CITY a few months later. And in the summer of 2023, I read Lynch on Lynch and Room to Dream.

This ranking system reveals that as of January 2025, three of my 75 favorite films – Lost Highway (#72), Inland Empire (#50) and Mulholland Drive (#6) – were directed by David Lynch. Not far behind are Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (#129) and The Straight Story (#184) and Eraserhead (#223). Do not take these rankings too literally, though, other than to say six of my 250 or so favorite films were directed by Lynch. Until his death, he was my 2nd favorite director overall – behind Alfred Hitchcock – and my favorite living director. That honor now passes to 54-year-old Christopher Nolan – my 3rd favorite director overall.

We now return to the conversation about video cameras from Lost Highway. Lynch often said that the “false” memory is more emotionally valuable than whatever the truth is.

I mostly disagree.

The basis of interrogating memory is learning the truth, however discomforting, while being willing to be proven wrong. To be fair, Fred Madison starts to do this at the end of the film. As does Betty Elms/Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts) at the end of Mulholland Drive. And – maybe? – Nikki Grace/Sue Blue (Laura Dern) at the end of Inland Empire. Laura Palmer must confront the grotesque reality of her father, sacrificing herself to save others at the end of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

Hold on a second. Given that I want to hold the movie camera, does that make me the Mystery Man (Robert Blake) in Lost Highway? Oy, that is a disturbing thought.

We also part company spiritually. Lynch was a devoted practitioner of Transcendental Meditation (“TM”) for five decades, while I am a metaphysical skeptic, to put it mildly. Indeed, Chapters 7 through 10 of Interrogating Memory document my journey toward critical thinking as much as toward film noir fandom. That journey begins, curiously enough, with a (possibly false) recollection that my mother forgot her TM mantra as soon as she came home with it.

But these are minor differences compared to two things Lynch and I share: a strong desire to show compassion toward all people (even when we disagree profoundly), and an unwavering commitment to our art. The former, ironically, was greatly shaped by my Jewish heritage, with its emphasis on the Biblically-sanctioned good deeds called mitzvot. Actively doing good deeds, the logic goes, is far greater than simply not doing bad deeds.

Perhaps Lynch’s warmth is best revealed by the coterie of performers – beyond Badalamenti and Cruise – who worked with him on at least three projects (counting the online series Rabbits as a distinct project): Jack Nance, Kyle MacLachlan, Dern, Michael J. Anderson, Sheryl Lee, Grace Zabriskie, Harry Dean Stanton, Naomi Watts, Laura Harring. In the #Metoo era, hearing female performers praise the supportive on-set environment he created is refreshing to the point of astonishing.

The latter was shaped for Lynch by his unpleasant experiences with the Hollywood studio system while making The Elephant Man (for which Lynch received his first of three Academy Award nominations for Best Director; he never won) and Dune. This is not to say every creative idea is good – more of them are awful than we like to admit, and we need a trusted person to tell us that honestly and directly.

Nonetheless, Lynch’s most profound insight was that when you get a particularly good idea – what he called catching the big fish – you need to see it through in your own way. Never prostituting yourself or your art is a key theme of Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. For better or worse, I purposefully chose to complete Interrogating Memory before seeking a literary agent and publisher. I wanted to enact my vision of the book without unwarranted interference in the name of…mass appeal, simplicity, whatever. Perhaps that was a bad (or, at least, naïve) decision, but it was my decision, and I am very proud of what I produced – with a great deal of pointed input from Nell, my most honest and direct critic.

There is one final way in which Lynch and I are similar artistically – and, yes, my non-fiction narratives are works of art, because all writing is. We both are willing to tell interesting stories – or include interesting scenes – only tangentially related to the overarching narrative. Think man with squeaky voice and hand-dancing lady in a bar scene in Wild At Heart. Or the botched killing of the man with the black book in Mulholland Drive. Indeed, much of the latter film feels like a tangent, given its origin as a television pilot.

In Interrogating Memory, I tell the stories of Harry Merrick III, Corinna Model, Edward “Psycho” Klayman and Lee Beloff, among others, that have nothing to with my becoming a film noir fan, but are still some of the best in the book. In fact, when I started to write the book in July 2017, I planned to center the book on film noir – using film titles as chapter titles, putting capsule summaries of relevant films in sidebars, and so forth. But as I researched the histories of my families, and I followed those ideas, the book evolved into an exploration of the exciting true stories we learn when we do the work to find them. Just as Inland Empire comprises a loose collection of stories, vignettes, really joined by the idea of history repeating itself in both art and reality. Film noir remained a key theme, of course, but alongside Philadelphia, Judaism and critical thinking.

Thus, and perhaps inevitably, we end in Philadelphia. Thank goodness Lynch got off the bus there…and may he now rest in peace, or whatever happens after death.

Until next time…and if you like what you read here, please consider making a donation. Thank you!

- Unfortunately, Newspapers.com does not include the New Haven Register. ↩︎

- This section drawn primarily from pp. 63-90 of Lynch, David and Kristine McKenna. 2018. Room to Dream. New York, NY: Random House ↩︎

- “Male Help Wanted,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), November 5, 1965, pg. 41 ↩︎

- Room to Dream, pg. 64 ↩︎

- Ibid. pg. 79 ↩︎

- Ibid. pg. 78 ↩︎

- Rea, Steven, “David Lynch, Artist,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), September 7, 2014, pg. H5 ↩︎

- Room to Dream, pg. 66 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 68 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 85 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 72 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 69 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 70 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 73 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 73 ↩︎

2 thoughts on “When David Lynch went to Philadelphia”