Since my previous post (March 31), I have been singularly focused (perhaps even obsessed) with on-line detective work: constructing family trees for my genetic family.

As I explained last July, I was adopted in utero; my “legal” parents, David Louis and Elaine Berger, brought me home to Havertown, PA when I was four days old. I was raised in a “Russian”[1] Jewish family of liberal Democrats in the Philadelphia suburbs, ultimately attending Ivy League schools, and earning two Master’s Degrees and a PhD. I now live in the largely Jewish and (mostly) liberal Boston suburb of Brookline, MA.

Still, my life had its share of speedbumps. For example, my father’s gambling addiction (fueled by the death of his iron-willed mother) led him to lose the successful West Philadelphia business his father and uncle had acquired and nurtured for decades. That in turn led my mother to divorce him when I was in high school. Less than a year later, he would suffer a massive, fatal heart attack at the age of 46 (in the summer before my junior year of high school).

Each of these influences combined within my psyche to produce my current sense of identity—my internal answer to the question “Who am I?”

In no particular order, here are ways I would fill in the blank after “I am a ______”:

- Husband and father (albeit after 40 years of processing my parents’ issues)

- Data geek (“math whiz;” inveterate puzzle solver)

- Critical-thinking skeptic (liberal education, particularly in epistemological aspects of epidemiology)

- Liberal (sub)urbanite

- Jewish-raised atheist (see #3 above)

- Gambling opponent (my father’s experience; studying probability)

In that same July 2017 post,, I described how Nell had convinced me to do genetic testing through 23andMe, despite my considerable hesitation.

One reason for hesitating was this very question of identity.

For not only did I have 50-plus years of innate abilities, family history, education and geography filtering through my psyche, I also had the life-long capacity—due to the unknown story of my conception, as opposed to my adoption—to be both a part of my family and separate from it.

The details of my conception (beyond basic physiology) remain a bit murky. The story I had always heard (likely embellished along the way) went something like this:

An attractive unmarried Philadelphia woman, 18 years of age and of Scots-Irish ancestry, has an adulterous sexual liaison with a married older man of 28 who already has three children. Given that I was born on September 30, 1966, the act resulting in my conception most likely occurred in late December 1965. Who seduced whom is unknown. The man with whom she has these illicit relations came from Colombia. The timing of my conception suggests a “holiday party accident” fueled by alcohol and/or other illicit substances. One of my genetic parents (my guess would be my mother) has a Native American grandparent or great-grandparent. Unable and/or unwilling to raise the child herself (and this being nearly seven years prior to the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion nationwide), she chooses to place her baby for adoption. The adoption itself was arranged by the young woman’s older, savvier, even more attractive sister, who somebody in my legal family met or saw in the corridors or maternity ward of Pennsylvania Hospital, where I was born. All records of my adoption were then destroyed in a fire at the adoption agency my legal parents used.

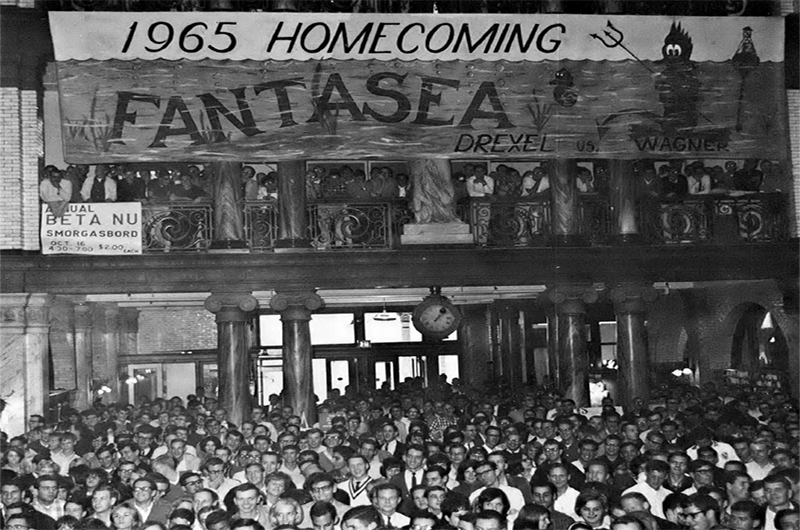

I have since learned from a maternal aunt that my adoption was arranged by a private lawyer named Herman Modell and that my genetic father was a graduate student/teacher at what was then called Drexel Institute of Technology. My working hypothesis remains that my genetic mother was a freshman at Drexel, as this is the least complicated way they could have met.

For all I know, one or both of my genetic parents is somewhere in this photograph (which I found here).

When I wrote that July 2017 post, I had not yet received my 23andMe test results. They landed like a missile in my Inbox on August 26, 2017.

I have not written about them before now because I am writing a book, in which I use the roots of my passion for film noir to explore my own backstory/ies and identity/ies, again seeking to answer the question “Who am I?”

But I do not want to give too much away in advance of hoped-for publication.

All of which brings me back to the last two-plus weeks.

Among the things I learned last August is that the “fact” that my father was Colombian is almost certainly not true[2]. With 50% confidence, 23andMe believes that I am 0.1% Iberian (Spain and Portugal) with a fully Iberian ancestor sometime in the 18th century; an additional 0.4% is “Broadly Southern European.” Moreover, I am 0.0% East Asian and Native American[3].

So…no Colombian and no Native American[4].

Pfui.

On the other hand, I am 51% British/Irish, heavy on the Irish. The rest is about half French/German (very likely Neanderthal—meaning from the Neander region of Germany) with a smattering of Scandinavian and that barely-perceptible (one strand of one piece of one chromosome pair) Iberian—with the remainder “Broadly Northwestern European.”

Basically, I am like the whitest white man ever. Or, at least, that is how I continue to process this information. I grew up loving the fact that I was a “walking United Nations”: of mixed Scots-Irish, Colombian, Native American ancestry, raised by a “Russian” Jewish family with a Greek first name, Anglo-Saxon middle name and German last name.

While all but two of those aspects remain, the loss of the Colombian and Native American aspects was profoundly disappointing.

Fun fact: while I was raised by Ashkenazi Jews, I am 0.0% Ashkenazi Jewish. My old-New-England-family (on her mother’s side), Episcopalian-raised wife, however, is 0.2% Ashkenazi Jewish.

She is having a (gentle) field day with this bit of irony.

Mitigating my disappointment was that my health reports were neutral (in a good way): no increased genetic predisposition to incurable diseases like Late Onset Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

And an unexpected fringe benefit of 23andMe genetic testing is the “DNA Relatives” report. Currently, there are 1,034 members of the 23andMe community with whom I share more than 0.25% of my DNA. Every one of these people is “predicted” to be no more than a 5th cousin (meaning we share a common genetic great-great-great-great-grandparent).

Last summer, as I was taking the genetic testing plunge, I was also starting to learn whatever I legally can about my genetic parents. On September 18, 2017, in response to my requests for identifying and non-identifying information about my genetic parents (along with $200—a savings of $100 over two separate requests), the Orphans’ Court of Delaware County (the venue in which my adoption was litigated) officially asked Delaware County’s Office of Children & Youth Services (CYS) to locate the records of my adoption and take the necessary steps to send me whatever information they have and can get consent to release.

According to my CYS contact, a “packet” was mailed to me today (April 16, 2018). This packet was supposed to arrive in mid-January (120 days after September 18, 2017), but I waited until mid-March to call CYS.

Basically, in the rush of late year holidays and my epic trip to NOIR CITY 16 (start here and read forward, if you are interested), I put the matter out of my mind. Plus, I had more than enough other bits of book-related history (Freemasons! West Philadelphia’s Jewish community! Times Square!!) to keep me occupied.

Then a wicked cool thing happened.

At the same time that I realized that my requested information was more than 60 days overdue, the first genetic relative closer than “2nd cousin” appeared on my 23andMe DNA Relatives list.

Since last August, I had the notion in the back of my mind that if the Orphans’ Court would/could not reveal the names of one or both genetic parents to me, I could very likely reverse engineer my genetic family through my DNA Relatives. Especially because I can also see, for each DNA Relative, any other listed surnames (read: female ancestor maiden names) and every relative with whom we both share genes.

But not only did a number of “1st cousins” debut on my DNA Relatives list, I shared a maternal haplogroup with one and a paternal haplogroup with another.

In other words, I knew that the first one and I had (genetic) mothers who were sisters[5] and the second one and I had (genetic) fathers who were brothers.[6]

More to the point, given American nomenclature traditions, I knew the last name my genetic father had (or, at least, HIS father’s last name).

Huzzah!

This, then, is the detective work—a whirlwind of Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com (so much information in obituaries), Google (WhitePages, Spokeo, PeopleFinder, etc.) and Facebook (“Friends” lists are powerful research tools), plus simple inexorable logic—I have been conducting since I last posted.

And in these two weeks, I have learned nearly everything I can about my genetic families—except the names of either genetic parent. Based on the family trees I have carefully constructed (and confirmed), I know to a near-certainty the names of my genetic maternal grandmother and paternal grandfather, as well as the names of their other offspring.

But I cannot find the relevant offspring, who I suspect were themselves placed for adoption (or, in at least one case—if not both—raised by other family members).

Are you freaking kidding me?

It is as though I can tell you every last detail of a house…except the names of the couple that actually lives there.

This house—my ancestry—mostly consists of rural white Christians (lots of Baptists, from what I can see) from the southern United States (Georgia, Florida and Kentucky, especially), a handful of whom fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

It is funny. I identify strongly as a “Northerner,” primarily due to my years spent in Connecticut and Massachusetts. But my native Philadelphia is not THAT far north and east of the beginning of the Mason-Dixon Line, separating “free” and “slave” states.

Nonetheless, I am struggling to reconcile my “Northern” identity with my “Southern” genetic ancestry, even if that ancestry plays about as much role in my current identity as a toy factory assembly line worker does for a doll from that factory.

The book is one reason I have refrained from discussing what I have learned. Another reason—perhaps a better reason—is my wish to protect the privacy of newly-discovered genetic relatives. My direct communications with some of them have been remarkably pleasant, even welcoming; I do not want to jeopardize these nascent connections.[7]

So I will share one piece of craziness with you, while still maintaining my genetic relatives’ privacy.

When I realized that I almost certainly knew my genetic father’s last name, I began to search for someone with that name who was a graduate student at Drexel in 1965/66.

Almost immediately, I stumbled upon a male “Firstname Y. Lastname” who submitted a MS thesis (applying advanced statistics to engineering, no less) in 1965. A man of the same name (with a middle name fitting the initial on the Drexel record) was born in April 1938, making him the exact age as in my “origin story.” He had won a scholarship to a prestigious northeastern university, graduating at about the right time, while his younger would brother would attend Yale University (as would I less than 20 years later).

He had also divorced his first wife sometime between 1964 and 1969 (she become a renowned academic in her own right), which just added fuel to the speculative fire.

However, when I stepped back to look at the bigger picture…connecting the dots of other also-related DNA Relatives (and looking more closely at where he would have been living in 1965-66—only a 90 minute or so drive away, but still), it became apparent that this was not the correct man. At least, not if his ascribed parents were also his legal parents (I remain open to the possibility that he was a “love child” raised by distant cousins).

In other words, “Firstname Y. Lastname” is either the greatest red herring I have ever seen, or he IS my genetic father, but was actually raised by his fifth cousin, once removed.

That “packet” from CYS cannot get here quickly enough.

Until next time…

[1] Meaning “from the Pale of Settlement region of the late 19th/early 20th century Russian Empire,” as my forebears actually hailed from modern-day Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine.

[2] Perhaps he had come from Columbia University or Columbia, MD, and my mother misunderstood?

[3] At 90% confidence: 13.8% British/Irish, 2.4% French/German, 62.9% Broadly Northwestern European, 18.9% Broadly European, 1.9% Unassigned.

[4] I would observe that all of the nations listed in “Native American” are south of the United States. There is still, then, the tiniest glimmer of hope for some Native “United States/Canada”

[5] Or a mother and maternal grandmother who were sisters

[6] Or a father and paternal grandfather who were brothers

[7] Moreover, there is always the very small chance that 23andMe, despite every precaution, made a mistake somewhere. That situation would not be helped by me acting like a blabbermouth.

You have had much more trouble than I did tracking down my biological family. In Texas, we have this website that allowed me to input my birth certificate number and within 2 days, somebody emailed me with my families names. I wish you had something like that! Your book may have not been written though as it was a bit too easy after 40 years of wondering for me.

I’ve now met my siblings and moved on. Both of my biological parents were 16 when I was born and both have passed (one of hiv and one of ovarian cancer) but I’m glad I got to meet my half siblings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow what an amazing story! It must have been so thrilling every time you found an answer to a question. It sounds like you are a very patient person!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Patient…obsessive…take your pick. 😆

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m enjoying reading about your journey. I hope you find all that you are looking for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Margie, I have hit more dead ends than the Minotaur’s labyrinth, but the journey has been a hoot. 🙂

LikeLike

Matt, thank you for filling in so many blanks. I look forward to having you as my nephew!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are very welcome.

LikeLike